Gliderunning: Part 6: Upper Body

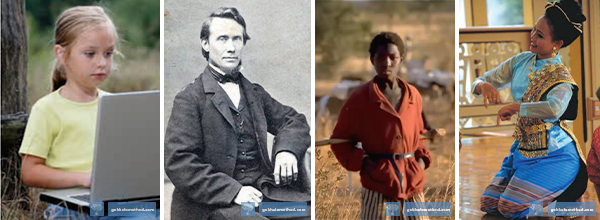

Welcome to the sixth blog post in our series on running. My name is Michelle Ball, and I am a Gokhale Method® teacher living in Tasmania. I am also a lifelong runner and am passionate about sharing the benefits of healthy posture with the running community, be that beginners, seasoned runners, or anyone in between. Even if you walk rather than run, the posture principles outlined in this post can still help you to enjoy an active and pain-free body well into old age.

Running with a well-positioned upper body

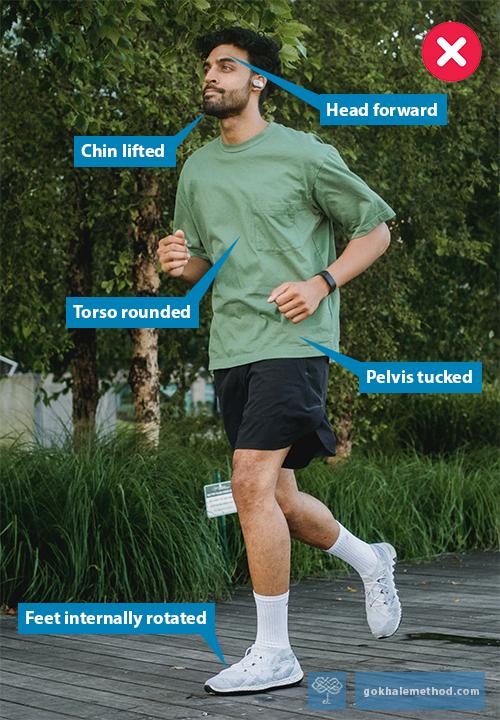

In this post we will consider the upper body. Runners are inclined to pay far less attention to the upper half of the body than the lower half, as they focus on gait pattern, cadence, footwork, and propulsion. This is hardly surprising, but the lower body, while super-busy, really is just half the story.

Healthy posture in the upper body brings the following benefits:

- Protected spinal structures

- Improved biomechanics

- Unimpeded flow and momentum

- Support that makes the body feel lighter

- Athletic appearance

Healthy posture principles are important for the upper body as well as the lower. Implementing them can both protect your spine, and bring mechanical advantage to your running. Unsplash

I have found the upper body principles that we teach in the Gokhale Method® in-person Foundations and Pop-up courses, and our online Elements course, made a world of difference to my running. Let me share some key points with you. . .

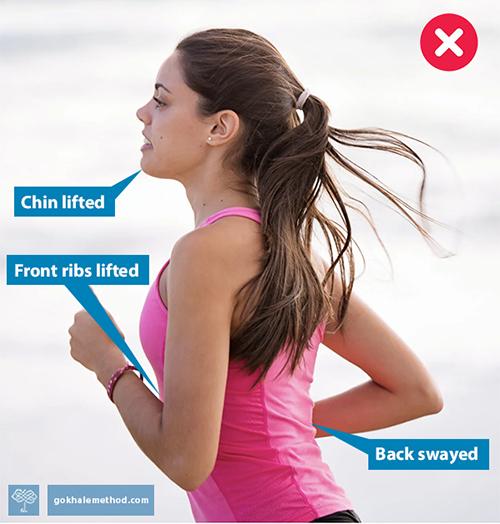

Anchoring your ribs

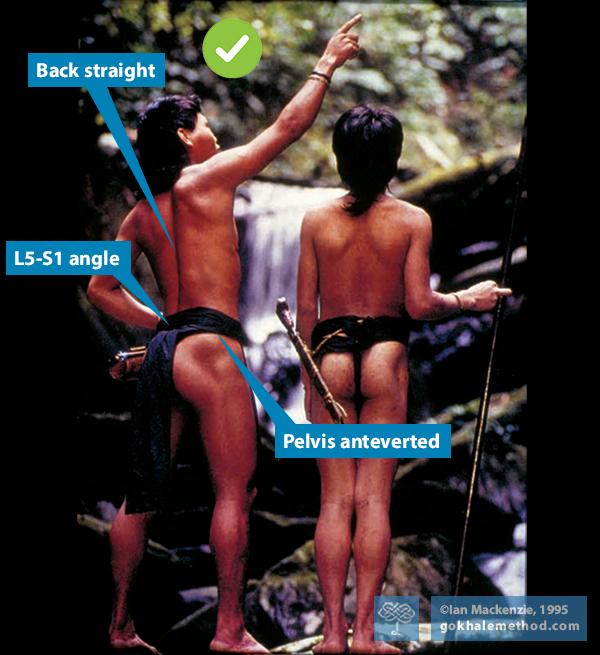

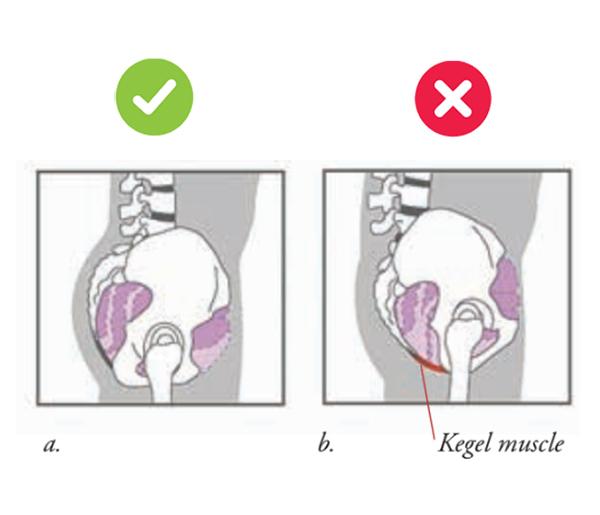

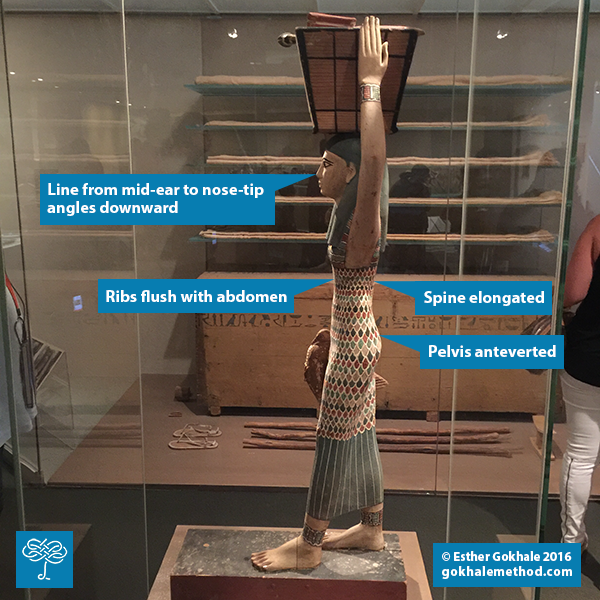

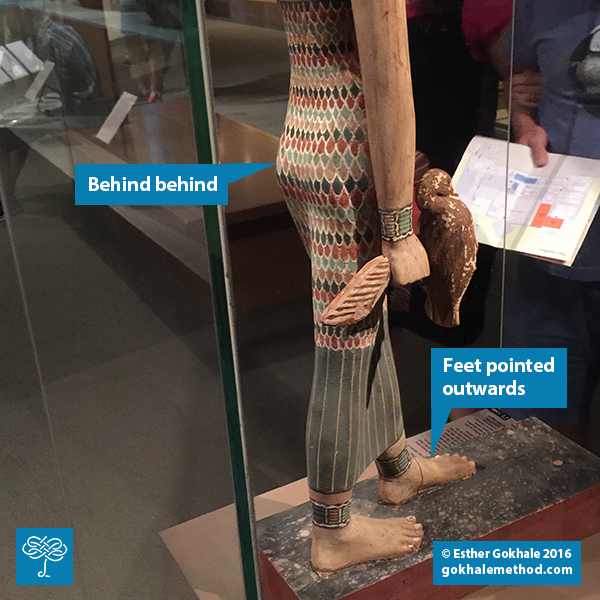

As explained in my previous post, Running: Part 5: Anteverted Pelvis, a forward leaning position when running helps to avoid compression in the lower back. In our culture it is common that people have tight lower back muscles (erector spinae), and weak opposing muscles of the torso (internal obliques). This creates a sway back, which pulls the torso into a backward leaning position. A deliberate forward lean will help counter this.

Here you can see me keeping a consistent forward angle throughout my torso, neck, and head.

Most people will benefit from some degree of forward rotation of the thorax to fully correct a sway and bring their torso into a straight and healthy alignment. This adjustment can be made and maintained by engagement of the internal oblique muscles, or rib anchor, as we Gokhale Method teachers call it. The rib anchor can be learned with a simple but precise maneuver which you can learn here.

Overly contracted back and neck muscles can give a misleading feeling and appearance of being upright. In reality, overly muscles are pulling the lumbar and cervical spine into compression, threatening discs and nerves. Pexels

Deeper support and protection for your spine

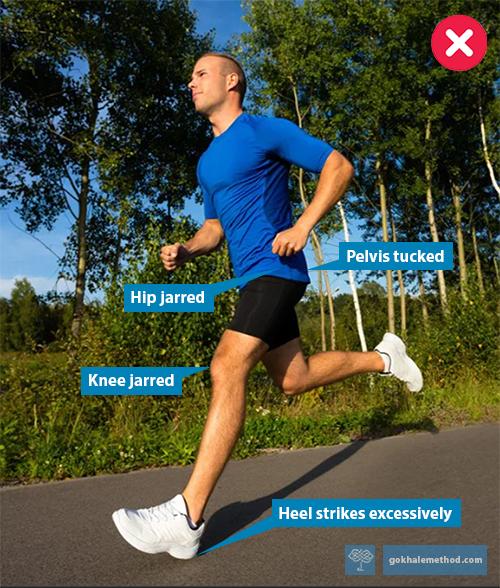

Running is classed as a “high impact” activity. This is one reason to run with the best posture and technique you can. Even if you are running smoothly with impeccable form, running will generate additional forces that impact the spine on landing. Perhaps that is how “jogging” got its name!

Using your inner corset while running lends natural protection to the joints, discs, and nerves of the spine in two important ways. Firstly, it creates and maintains length, and secondly, it confers stability, preventing untoward twisting, forward, back, and sideways movement. The trunk and pelvis remain a single unit, with no jiggling from micro-flexing and extension, or bobbing up and down—and the head travels at a continuous level, sparing the neck. In these respects good running form is the same as good walking form. The spine and its tissues are saved from both acute injury and long-term wear and tear. How to find and deploy your inner corset is explained in detail in Esther’s bestselling book, 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back.

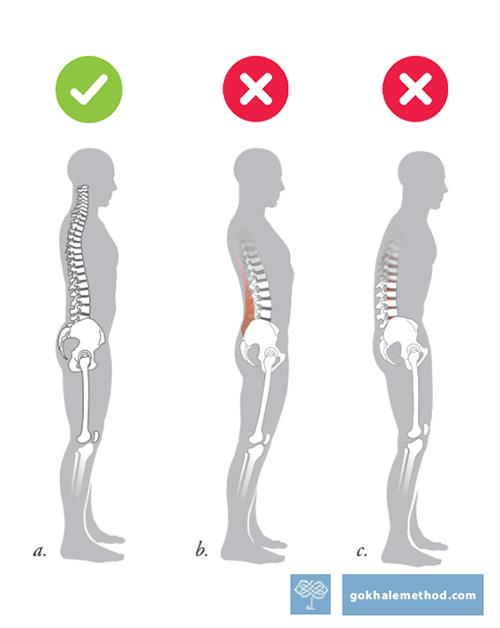

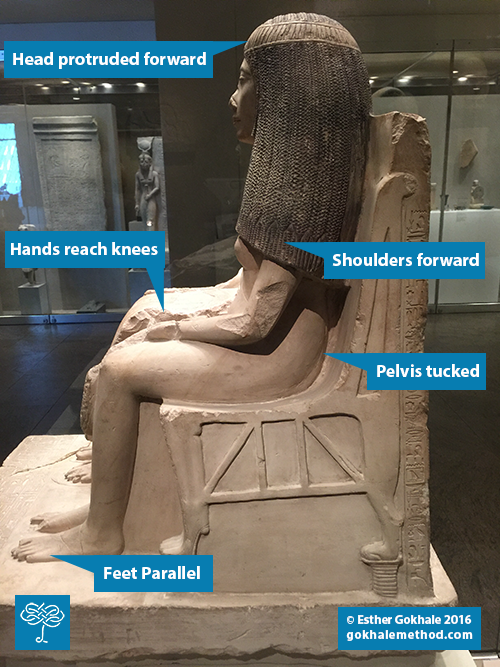

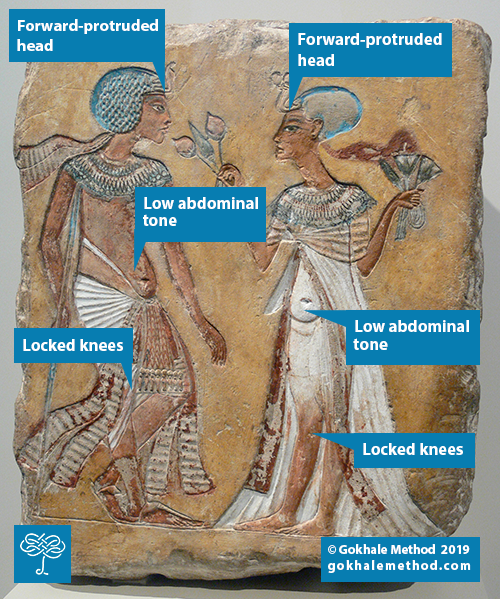

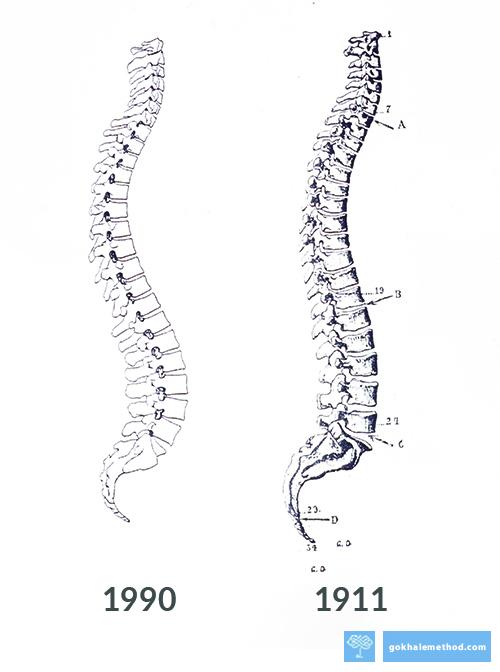

These two medical illustrations from 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back show how, in modern times (e.g., 1990), deeper spinal curves have come to be regarded as normal and desirable. The Gokhale Method advocates a return to a straighter, longer spinal shape (e.g., 1911).

Avoiding neck pain while running

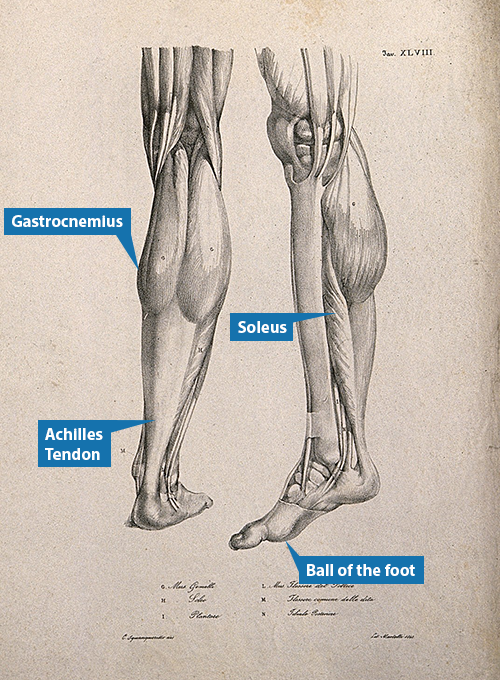

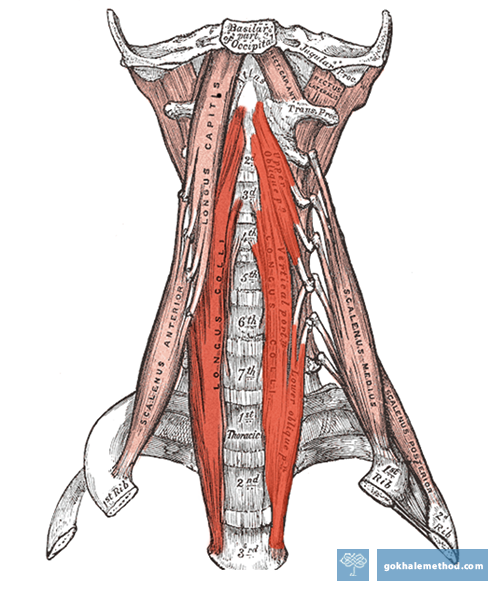

Deep engagement of the inner corset will preserve length in the lumbar spine, and this supportive structure also encourages length in the cervical spine, or neck. In addition, locally, the longus colli muscle, which attaches to the front and side of the neck and upper thoracic vertebrae, needs to be engaged to draw the neck back into a tall, lengthened position in line with your body.

The longus colli muscle (seen here in red) draws the vertebrae of the neck back into a healthy, tall, and spacious alignment. Wikimedia

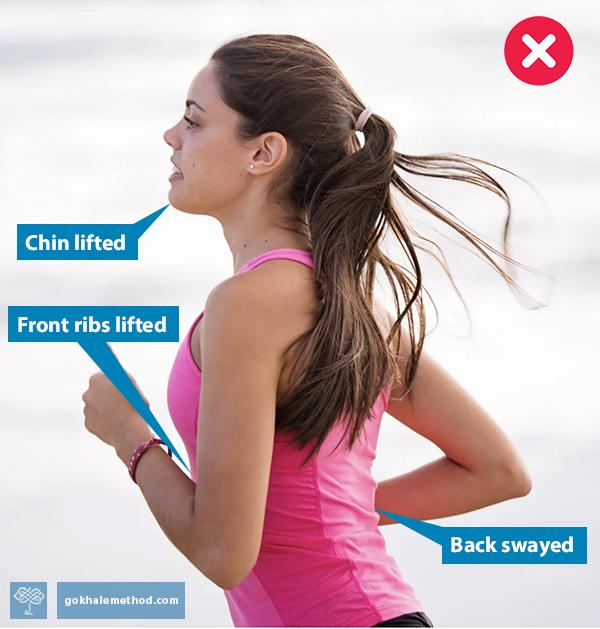

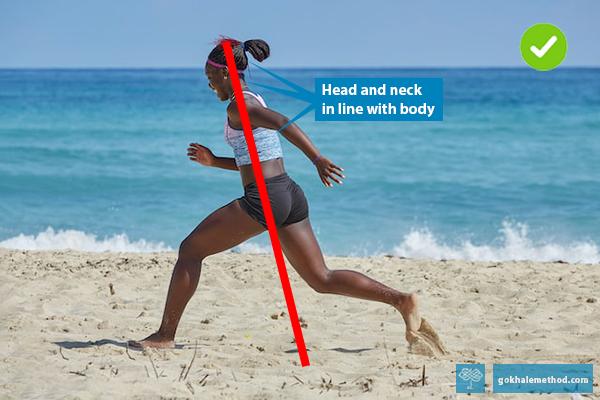

Gliding your head up and back, while allowing your chin to rest down, will provide stable and relaxed carriage for your head, and a happier neck. You can learn how to glide your head back here.

Your head and neck want to remain back in line with your body, even as you lean forward.

You don’t want to jut your chin forward and let your head literally run ahead of you. Pexels

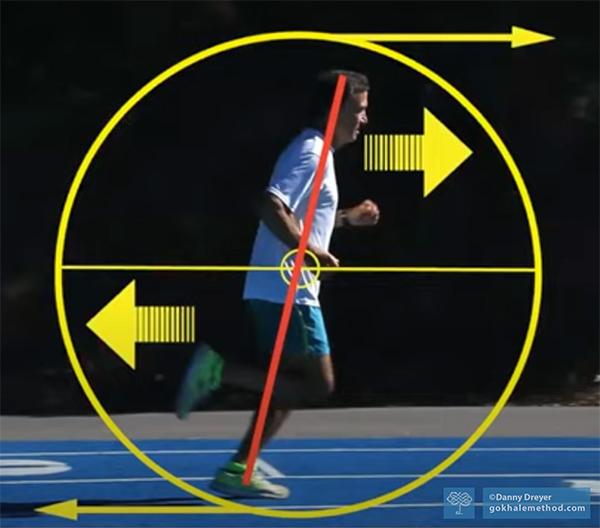

Trunk stability

The trunk stability that protects the spine also enables efficiency when running, as energy is not dissipated into incidental movements that detract from forward motion. It enables all propulsion to be well channeled, rather than just pulling the spine around. As running expert Marc Cucazella reminds us, “You can’t fire a cannon from a canoe.” In the upper body this propulsion comes from the arms.

Arm movements in running

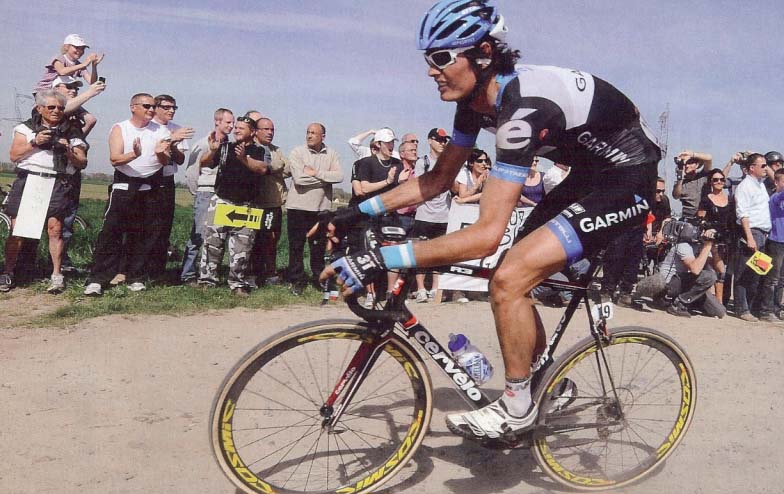

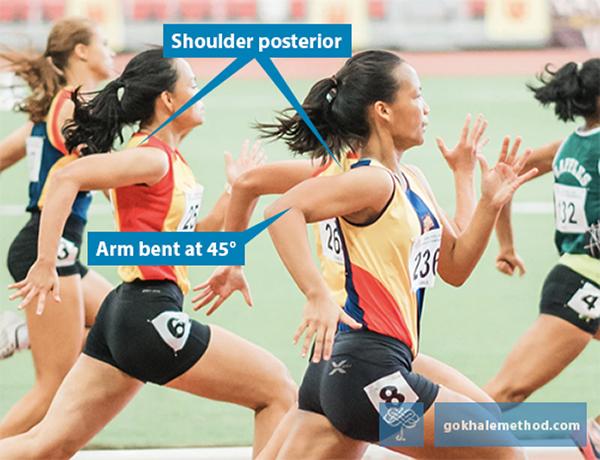

Whereas in glidewalking the arms largely rest, in running the arms actively contribute to propulsion and alternate with the leg action. In sprinting the arms are especially important, moving straight forward and back like pistons on either side of the body. The arms are bent at 45 degrees or slightly more, with the hands moved in a circular, rearward pull motion, as if you were chopping wood. The arms then recoil forward, very slightly rotating the shoulders. What you don’t want is the arms to be crossing the midline of your body and pulling you off balance. Arm action can be much more relaxed at an easy jogging pace or in distance running.

The vigorous piston action of the arms in sprinting requires a well-configured shoulder joint. Unsplash

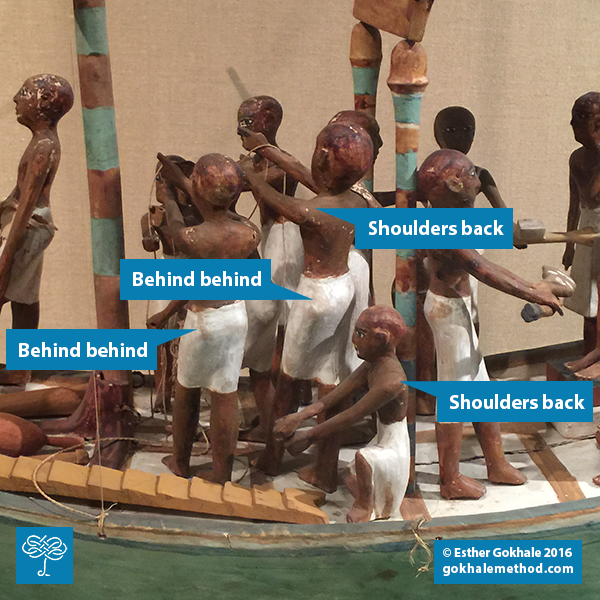

Whatever your running speed, it is extremely important that the shoulders be well positioned, so that the joint—where the bone of the upper arm, shoulder blade, and collarbone meet—can connect well, and the soft tissues, nerves, and circulation can function optimally. You want your shoulders to be happily at home in their natural, posterior position. You can learn how to roll your shoulders back here.

Open, posterior shoulders will also help you to access breathing in your upper chest. If you tend to hunch forward, draw your elbows more together behind you to assist the external rotation of your shoulders.

Relaxed and bouncy shoulders

In gentler jogging and long distance running, the shoulder area can be more relaxed. Healthy alignment within the shoulder joint is still important for the hundreds of to-and-fro arm reps, and to cushion the impacts traveling through the joint with every stride. A healthy postural relationship between the upper back, the shoulder girdle, and the neck will help the shoulders to be responsive rather than held tight, and to bounce a little as you run.

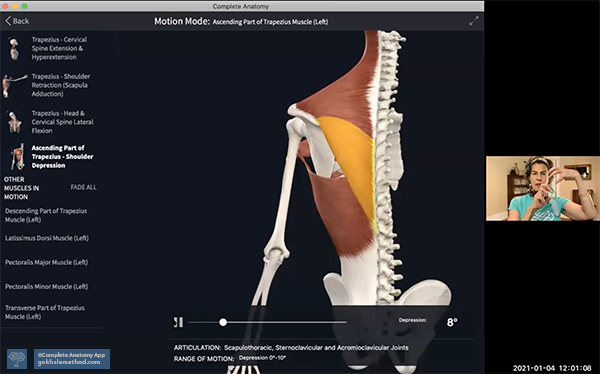

The trapezius muscle is at the center of healthy upper back, neck, and shoulder posture. It helps the shoulder to lift, lower, and gently bounce through impactful movement. Wikimedia

Stick or twist?

The synchronized alternation of arm and leg movement is vital for momentum and balance during running. This will be integrated by the torso twisting somewhat. There is a counter movement of pelvic rotation backward as the chest moves forward on the opposite side. The key is neither to over stiffen, nor over twist the torso. A stiff body keeps the hips from extending fully, can shorten your stride, and puts more pressure on the knees and leg joints. Over twisting can cause a “sloppy” run and impinge on the spinal joints. This is where staying tall with a strong inner corset is invaluable, as the inner corset allows healthy rotation both through and beyond it.

In particular, avoid an upper/lower torso separation with twisting happening almost entirely at the T12/L1 junction, where the ribs meet the lumbar area. Twisting here is sometimes misguidedly encouraged to help power the arms, especially in fitness walking classes. However, there is no ball and socket joint at T12/L1 that makes swiveling here a good idea for the spine!

This runner’s torso shows considerable rotation, but it is distributed along the spine—it does not twist at just one point. South African sprinter Wayde van Niekerk sets a world record at the 2016 Olympics. Alessandro Bianchi / Reuters

Olympic gold medalist Tirunesh Dibaba also shows even rotation of her torso from hip to opposite shoulder. I’ve also noticed that most East African runners have a significantly higher arm carriage, and are among the best runners in the world. Bretta Riches – Run Forefoot

If you would like guidance on any aspect of your posture and/or running, including your head, neck or shoulder position, consider scheduling an Initial Consultation, online or in person, with a Gokhale Method teacher.

6-Part Gliderunning Series

- Read Part 1: Introduction.

- Read Part 2: Meet Your Feet.

- Read Part 3: How to Choose Running Shoes.

- Read Part 4: Taking Care of Your Knees.

- Read Part 5: Anteverted Pelvis.

- Read Part 6: Upper Body.

If you would like to find out more about how the Gokhale Method can help support you, sign up to join one of our upcoming FREE Online Workshops.