Why so much pain and dysfunction?

As a society, we have lost touch with our blueprint. Our modern lifestyles have led to detrimental changes in the ways we sit, stand, walk, bend, and more. These changes in activities we do all day, every day, are at the root of most of the musculoskeletal pain we see around us.

Changes in the way we sit, stand, walk, and bend are at the root of most of the musculoskeletal pain we see today.

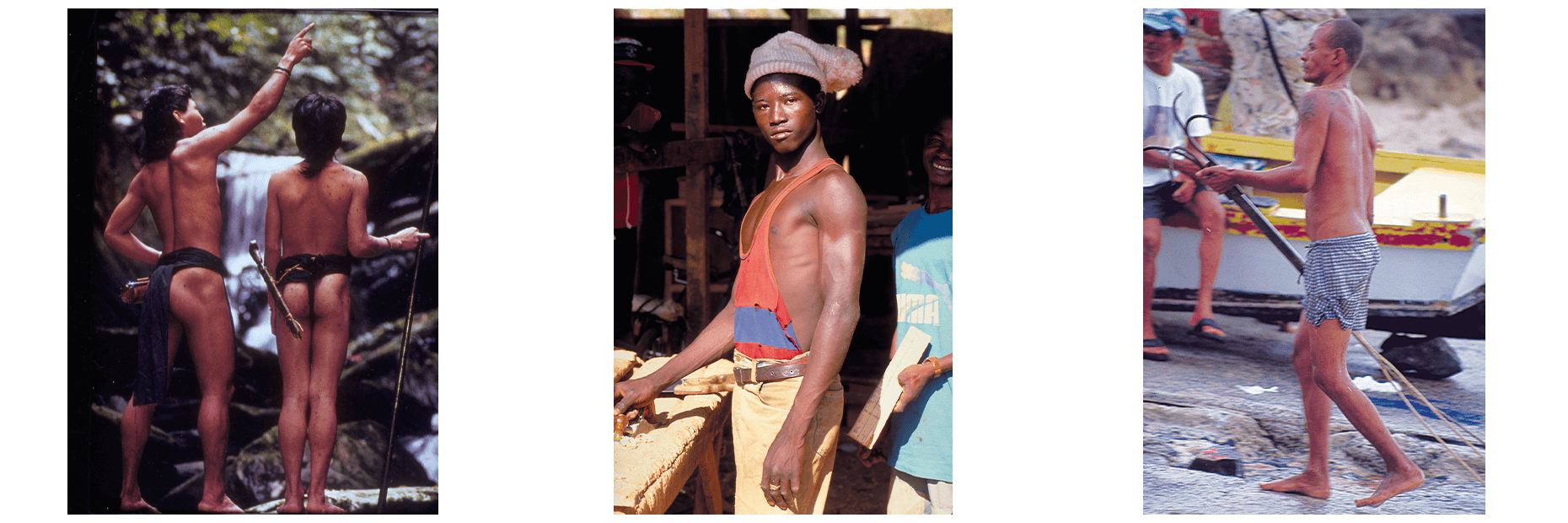

Modern conventional wisdom is based on the incorrect assumption that the human spine is S-shaped. Everything in modern culture is built around this S-spine paradigm—from protruding head rests in our car seats to lumbar support in our ergonomic chairs to the way spinal fusion surgeries are done.

Many “ergonomic” chairs are designed to support pronounced curvature in the spine.

The Gokhale Method teaches that the natural shape of the human spine is closer to a J than an S. This is what we see in ancestral populations, non-industrialized cultures, and young children the world over.

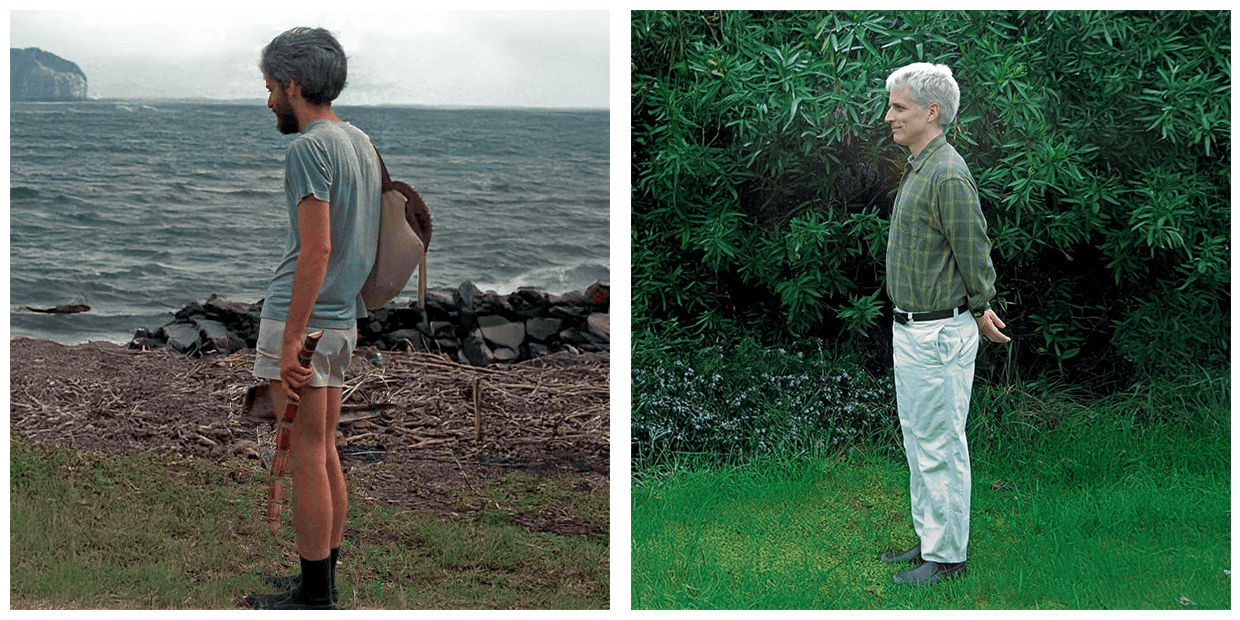

Our great-grandparents sported J-spines.

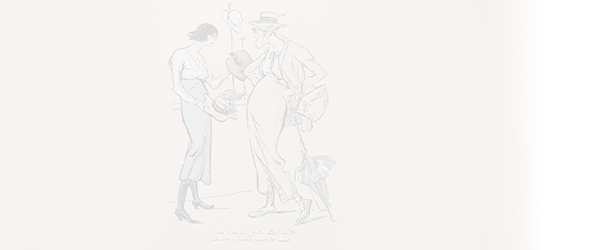

People in non-industrialized societies sport J-spines. Indonesia (left), Burkina Faso (center), Brazil (right).

These are very different populations—why would they all share a spinal shape? The simplest explanation is that it is, in fact, the natural shape for human spines.

When you were two years old, you had this spinal shape, too!

This drawing from A Textbook of Anatomy, edited by Frederic Henry Gerrish M.D., Professor of Anatomy, Medical School of Maine, 1911, shows that we used to recognize that the human spine is shaped like a J.

Furthermore, when we consider the biomechanical stresses on the nuts and bolts of the spine, the soundness of the J-spine is compelling, see “An S-shaped Spine Is A Compressed Spine”.

You may well wonder how a society’s understanding of something as fundamental as spine shape could drift over just a few decades. Here it’s helpful to consider our natural human tendency to mistake average for normal. At the Gokhale Method, we invite you to consider that the S-spine paradigm that is ubiquitous in modern culture and medicine is only a description of the average human spine shape today, not the truly natural human spine shape.

Your next question may be why the average human spine shape as depicted in modern anatomy books is so different from what we see from the early 20th century. One likely contributor to this posture drift is the fashion industry. Around World War I, fashions in clothing and furniture began to change, reinforcing a trend towards slouching as being “casual” and “cool”.

This 1919 caricature of Coco Chanel in the album "Le grand monde à l'envers" by Georges Goursat shows the emerging penchant for thrusting the hips forward, thus contorting the spine into an S-shape. This posture is still common on modern catwalks as well as everyday settings.

In modern times, we have furniture, clothing design, fitness recommendations, medical interventions, and more, all contributing to this postural distortion and drift. It is therefore not surprising that so many of us experience pain and dysfunction.

We won’t solve the back pain epidemic by continuing down the S-spine road. Instead, we want to revert to the older, wiser ways of our great-grandparents and other cultures who were more successful with their backs.

The Gokhale Method teaches you how to sit, sleep, stand, walk, and bend in the way all humans are meant to—with a J-spine. In relearning how to position your body for these everyday activities, you’ll re-architect your shoulders, arms, neck, torso, hips, legs, and feet for success rather than failure.

Optimal architecture facilitates optimal function; our everyday movements then become constructive rather than destructive.

An S-shaped spine is a compressed spine

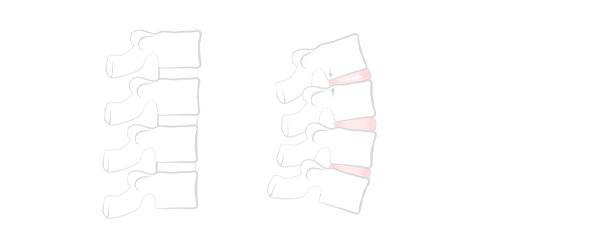

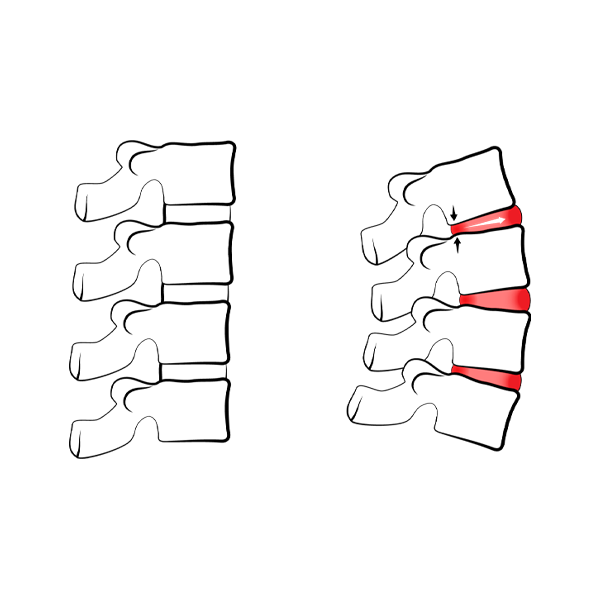

When the spine curves excessively, for example in the lumbar (lower back) and cervical (neck) sections of an S-spine, the spinal discs are compressed. Compression can cause wear and tear, dysfunction, and pain.

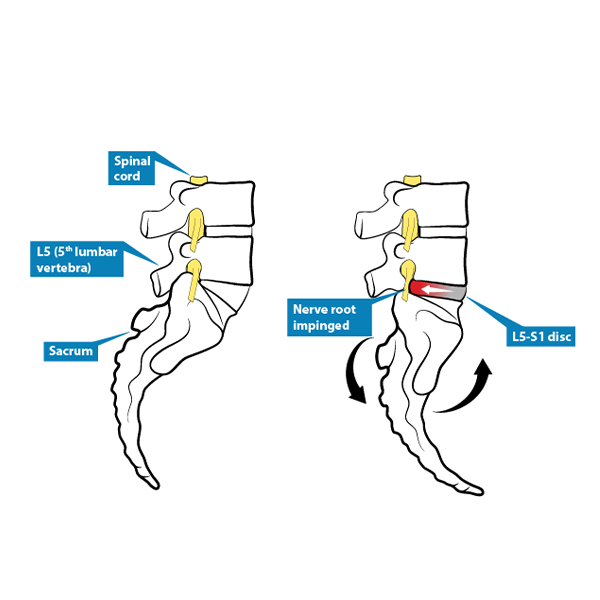

The common guideline to “tuck the pelvis to protect the lower back” in fact compresses the lowest disc in the spine (L5-S1) anteriorly, causing the disc to protrude posteriorly. In the worst case scenario, the disc impinges on the roots of the sciatic nerve. Tucking the pelvis also predisposes to gluteal weakness, arthritic changes in the hips, rounding and tension in the upper body, and other problems.

How are we meant to move?

If you lived a hundred years ago or in a village in rural Southeast Asia or Africa today, you would have a good sense of what healthy body architecture looks like. Living in modern industrialized societies, we’ve lost sight of how our bodies are supposed to function. Some principles we would like to put back in place include:

1. Every bone in its home

Our bones fit together in a precise way that is the product of the demands of upright living and the constant force of gravity over the span of human existence. Our weight-bearing bones need stress to remain strong. Without this stress, calcium leaches from the bones or is inadequately deposited, leading to osteopenia and osteoporosis. Weight-bearing exercise provides the healthy stress that keeps bones strong. However, stress on the wrong part of the bone, caused by misalignment, can lead to arthritic changes such as bone spurs (osteophytes).

The Gokhale Method shows you how to take each of your bones “home”. This reduces harmful stress and restores healthy stress to the bones.

In this “before” photograph (left), the legs, hips, and spine are misaligned and therefore lacking healthy weight-bearing stress. In the “after” photograph (right), the healthy stacking of these bones results in healthy weight-bearing stress.

2. Muscles fully relaxed when not working

Many of us spend hours tensing our muscles unnecessarily. In fact, in modern societies it is a common notion that sitting and standing up straight require significant and sustained effort. This tension is usually a compensation for poor alignment and often becomes habitual. Our students are surprised to find that they can sit upright with as little effort as it takes to slouch.

No muscle is meant to be on all the time. The Gokhale Method teaches you to use only the muscles needed for a certain action and relax the rest. This relaxation facilitates vigorous action when it is actually needed.

Sitting and standing the way we are meant to is surprisingly relaxed and effortless

3. Use the muscles, spare the joints

The man on the left lands with a straight knee and underuses his glute muscles. This leads to a heavy landing, putting stress on all the weight-bearing joints of the body. The woman on the right uses strong gluteal muscle action to land gently and gracefully. She also lands on a bent front knee that cushions the impact of landing.

The Gokhale Method also teaches how to bend in a way that uses your muscles more and your joints less. Rounding the back when bending compresses the spinal discs and leaves the muscles of the back largely unchallenged. On the other hand, bending with a straight back (what we call “hip-hinging”) engages the long muscles of the back and spares the spinal discs and ligaments. Again, muscles gain strength while joints remain healthy.

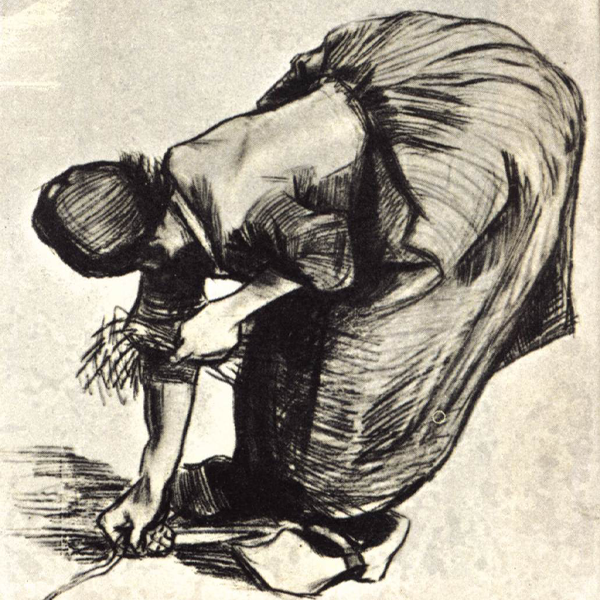

When Van Gogh drew this woman working on a farm in the 1880s, hip-hinging was the norm. Nowadays, hip-hinging is a rarity.

Hip-hinging is part of the traditional form of weightlifting and American football bends. This is because these traditions were established more than a century ago. And incidentally, it demonstrates just how robust hip-hinging is, as it is in these contexts that the human frame is put through some of its biggest challenges.

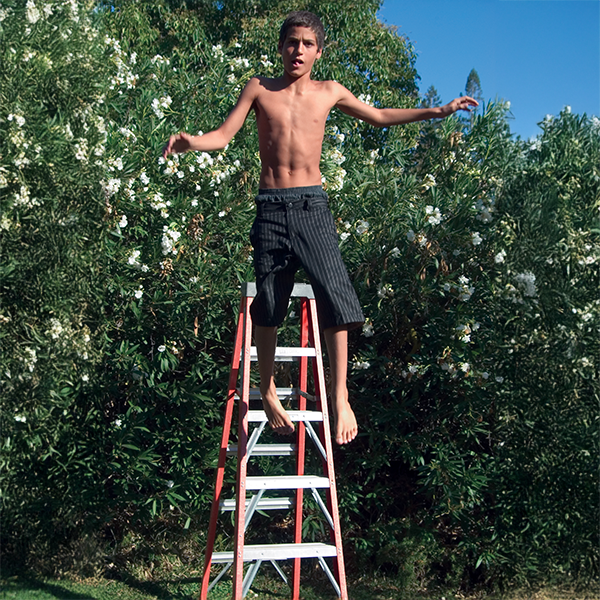

Your “inner corset” is another blueprint we can help you get back in touch with. If you were going to jump off a ladder, a precise combination of muscles would automatically engage to protect your discs, nerves, and bones from the impact of landing.

The inner corset muscles automatically contract in high-stress situations like jumping.

In the face of smaller threats of spinal compression or distortion—for instance carrying a heavy handbag or bags of groceries—we tend not to recruit this protection. The cumulative low-level wear and tear that results can be debilitating. Like glidewalking and hip-hinging, inner corset is a technique that takes stress off the joints (spinal vertebrae) where it would be harmful, and puts it on the muscles (abdominal and intrinsic back muscles) where it is beneficial.

Something approximating the inner corset technique is likely why an X-ray study of the Bhil tribe in Central India revealed that the disc heights of the 50-year-olds looked very similar to those of the 20-year-olds. In our culture, by contrast, it is considered normal to have significant disc degeneration by age 50.

This graph23 shows a large difference in disc narrowing with age in three different populations. Very little disc narrowing occurs in the Bhil tribal people of Central India24. Substantial disc narrowing correlates with older age among Western workers, in both industrial and forestry jobs25 and sedentary jobs26

The Gokhale Method invites you to raise your expectations of what your body is capable of achieving without pain or damage.

4. Take advantage of “life exercise”

The Gokhale Method is unlike any other approach in that we focus on “life exercise.” There is little need to take extra time out of your day to perform conventional strengthening or stretching exercises. Instead, you learn to incorporate stretching and strengthening into the life activities you do every day.

Our bodies evolved to automatically satisfy our stretch and strength requirements as part of everyday living. When you reinstate your natural blueprint, these laws of nature take care of maintaining balance between different parts of your body.

When you walk, bend, and carry in the ways these activities are meant to be done, you will be “exercising” all day long.

We are rooted in science

Scientific principles underlie and inform the Gokhale Method. Our founder, Esther Gokhale, studied at Harvard University and has a biochemistry degree from Princeton University, and was inspired by Aplomb® and other anthropological approaches. Our methodology is grounded in biophysics and evidence-based body mechanics.

The Gokhale Method has been well received by medical professionals and is currently the subject of a randomized controlled trial by researchers at Stanford University. You can learn more about the trial and the science behind the Gokhale Method here.

Here are a few comments from prominent physicians and scientists about the efficacy of the Gokhale Method:

“The patients I have referred to the Gokhale Method have, without exception, found it to be life-changing.”

- Dr Salwan Abi Ezzi, M.D.

“The greatest contribution ever made to non-surgical back pain treatment.”

- Dr Helen Barkan, M.D., Ph.D., Mayo Clinic

“Every year, tens of thousands of patients undergo major back surgery, without any benefits. Using Gokhale’s novel techniques, many of these patients can quickly return to a pain-free life.”

- Dr John Adler, M.D., Stanford University Medical Clinic

“Esther Gokhale’s approach to preventing and treating back pain deserves the attention of the medical profession.”

- Dr Harvey Cohen, M.D., Ph.D., Stanford University

“I need to do things that make sense and that I can see results from. Esther Gokhale’s work is like that.”

- Susan Wojcicki, CEO, YouTube

“I think Esther Gokhale could single-handedly cut the healthcare budget in half if given the chance.”

- Eric Schoenfeld, Staff Data Scientist, Google

Based on lived experience

Many methods that address pain and dysfunction are grounded in theory—how the body should function. But the human body is incredibly complex; we believe that no one understands the workings of the human musculoskeletal system well enough to approach it in an abstract way. The Gokhale Method looks at populations that have highly functional body mechanics. Hence our techniques emulate the modes of movement that humans have been testing and refining for millenia. The proof that these techniques work is in the very low rates of pain present in populations who still use these modes1-9.

You can read about the experiences of people who have learned the Gokhale Method at Google Reviews.

Reclaiming your birthright and moving out of misery

Our mission is to make back pain rare again. Our founder, Esther Gokhale, and many of our teachers have experienced and understand crippling pain. We are passionate about helping others regain their quality of life and reach their full potential.

Get back to doing the things you love to do, unhindered by pain.

You can start learning the Gokhale Method today whether you are a couch potato or a professional athlete. Learning to use your body the way it was meant to be used can transform your life. Get back to moving without pain and dysfunction!

As a first step, we recommend attending a Free Online Workshop. Sign up now.

Over the last 30 years, the Gokhale Method has honed an approach that is an outlier in effectiveness and efficiency for relieving back pain. It uses life exercises and requires no special equipment or time away from your life. The effects are permanent and sustainable.

Our techniques have been featured in The New York Times, where Esther Gokhale was dubbed the ‘Posture Guru of Silicon Valley’. Esther has appeared on NPR and in the Chicago Tribune, Baltimore Sun, and The Guardian. She has been hired by corporations including Google, Meta, and NASA, endorsed by celebrities such as Joan Baez, Desmond Tutu, and founders of various Silicon Valley Companies, participated in athletic training programs including the 49ers and several Stanford teams, and recruited to train physicians at Stanford, Kaiser, Brown University, UCSF, and more. Esther’s book, 8-Steps to a Pain-Free Back was #2 bestseller on Amazon, has been translated into 10 languages, and has sold more than 300,000 copies.

References

- Volinn E. The epidemiology of low back pain in the rest of the world: A review of surveys in low- and middle-income countries. Spine. 1997; 22(15): 1747-54.

- Fahrni W.H. Conservative treatment of lumbar disc degeneration: our primary responsibility. Orthop Clin North Am. 1975; 6: 93 Comment end -101.

- Darmawan J., et al. Epidemiology of rheumatic diseases in rural and urban populations in Indonesia: World Health Organisation International League Against Rheumatism COPCORD study, stage 1, phase 2. Annals of Rheumatic Diseases. 1992; 51: 525-28.

- Darmawan J., Valkenburg H.A., Muirden K.D. The prevalence of soft tissue rheumatism. A WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. Rheumatology International. 1995; 15: 121-24.

- Wigley R.D., et al. Rheumatic diseases in China: ILAR-China study comparing the prevalence of rheumatic symptoms in northern and southern rural populations. J Rheumatol. 1994; 21(8): 1480-90.

- Dixon R.A., Thompson J.S. Base-line village health profiles in the E.Y.N rural health programme area of north-east Nigeria. African Journal of Medical Science. 1993; 22: 75-80.

- Anderson RT. An orthopedic ethnography in rural Nepal. Med Anthropol. 1984;8(1):46-59.

- Farooqi A., Gibson T. Prevalence of the major rheumatic discords in the adult population of North Pakistan. British Journal of Rheumatology. 1998; 37: 491-95.

- Chaiamnuay P., et al. Epidemiology of rheumatic disease in rural Thailand: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD Study. Journal of Rheumatology, 1998; 25: 7.

- Andersson G.B.J., Epidemiology of Low Back Pain. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1998; 69(sup281): 28–31.

- Freburger, J.K., Holmes, G.M., Agans, R.P., et al. The Rising Prevalence of Chronic Low Back Pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169(3): 251–258.

- Rubin D.I., Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Spine Pain, Neurologic Clinics, 2007; 25(2): 353-371.

- de Souza I.M.B., et al. Prevalence of low back pain in the elderly population: a systematic review. Clinics, 2019l; 28:74.

- Atlas S., et al. Evaluating and Managing Acute Low Back Pain in the Primary Care Setting. J GEN INTERN MED, 2001; 16: 120-131.

- Global Burden of Disease Study. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 Data. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2017.

- Hoy D., et al. "The Global Burden of Low Back Pain: A Systematic Analysis." The Lancet, 2014; 384 (9946): 971–981.

- Waddell, Gordon, and A. Kim Burton. Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-being? The Stationery Office, 2006.

- Bigos S. J., et al. Acute low back problems in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2009; 150(6): 447-458.

- World Health Organization and The Bone and Joint Decade, 2001.

- Deyo RA, Phillips WR. Low back pain. A primary care challenge. Spine. 1996; 21(24): 2826-32.

- Siambanes D, Martinez JW, Butler EW, et al. Influence of school backpacks on adolescent back pain. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004; 24(2): 211-17.

- Luo X, et al. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004; 29(1): 79-86.

- Fahrni, W.H., Trueman, G.E. Comparative Radiological Study of the Spines of a Primitive Population with North Americans and Northern Europeans, The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 1965; 47-B(3): 552.

- Jackson R.P., McManus A.C. Radiographic analysis of sagittal plane alignment and balance in standing volunteers and patients with low back pain matched for age, sex, and size: a prospective controlled clinical study. Spine. 1994; 19(14): 1611-18.

- Hult, L. The Munkfors Investigation. A study of the Frequency and Causes of the Stiff Neck-Brachialgia and Lumbago-Sciatica Syndromes. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 1954; Sup16.

- Fullenlove, T.M., Williams, A.J. Comparative Roentgen Findings in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Back. Radiology, 1957; 68: 572.