How to Bend and How Not to Bend

Round-backed bending is ubiquitous in modern urban culture. It damages the back. Recognizing this, many health advocates recommend bending at the knees. Done to excess or with poor form, this damages the hips, knees, ankles, and feet.

Surprisingly, poor bending form abounds even in fitness and wellness classes.

An insistence on touching the toes can be counterproductive and result in damage

People sometimes equate being able to touch the toes with flexibility. An imprecise and insistent pursuit of this kind of “flexibility” causes disc damage, hyper-extended spinal ligaments, and a lot of pain. Let’s examine do’s and don’t’s in bending more closely.

DO

- Come close in to your tasks and don’t bend if you don’t need to.

If you can accomplish your task without bending, don’t bend.

- Be sure your legs are externally rotated so there’s room for your pelvis when you bend.

If your thigh bones (femurs) are in the way of the pelvis settling between the legs in a forward bend, there’s no healthy workaround for bending. Widening your stance can help some, but a healthy bend needs external leg rotation no matter where your legs are positioned.

This Burkina baby has his legs externally rotated, making room for his pelvis and substantial belly!

- Maintain the shape of your back when bending

The spine carries precious cargo - like all the nerves and nerve roots that exit between the vertebrae - and these are threatened by major distortions of the spine.

In activities other than bending, some movement around a healthy baseline is healthy and desirable. Such movement stimulates circulation and helps maintain healthy spinal tissues.

For bending, I recommend strictly maintaining the baseline shape of the spine. Distorting the spine when bending loads the discs and can cause damage. It also sets a risky pattern for bends that involve weight-bearing. I recommend pure hip-hinging for all bends, whether in daily life or exercise. With practice, good form, and strengthened inner corset muscles, you will be able to move into sustained bending and lifting weights.

Women in the marketplace in village Orissa demonstrating excellent hip-hinging form.

- Maintain (or increase) the length of your spine when bending

You don’t want to load your discs when bending. This happens when rounding or swaying the back, or from additional muscle engagement while maintaining your baseline spinal shape. Using the inner corset (go here for a free download of Chapter 5 from 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back) while bending is excellent insurance against loading the discs unwittingly.

- Practice bending with a teacher and with mirrors

If you are accustomed to tucking your pelvis, it can be a real challenge to find the correct movement in the hips. Practice bending in front of a mirror, or, better yet, with a Gokhale Method teacher, so you get the feel of healthy hip rotation with a straight back.

Working with a teacher helps set a healthy hip-hinging pattern

Start off with small bends - pay attention when you are at the sink or making your bed. Keep your feet and knees pointed out 10-15 degrees, have your knees soft and only bend at the hips as far as you can before you start to round. At that point, enjoy the gentle stretch in your hamstrings and external hip rotators. Bend your knees if you want to go any further. For more complete hip-hinging instructions and images, refer to Chapter 7 of 8 Steps to a Pain Free Back or Back Pain: The Primal Posture Solution (DVD).

DON’T

- Don’t Round the Lower Back.

The most common mistake in bending is to round the back, either distributing curvature throughout the spine or concentrating most of it in one spot. If your pattern of bending includes rounding the lower back, this is a particularly risky mistake. Being at the bottom of the heap, the lumbar discs are already particularly vulnerable to wear and tear, bulging, herniation, and sequestration. Rounding the lower back while bending puts additional strain on them. The amount of loading is high because our upper bodies are heavy (especially our heads) and the lever arm is long (Torque = weight X distance.)

You may know people who bent to tie their shoelaces or perform some other seemingly innocuous task on the ground, and then couldn’t straighten back up. Those people were probably rounding their lower backs, possibly with the additional danger of a twist added in. The brain reacts to the threat / damage by seizing up muscles in the area. Ouch! In my classes I go so far as to say that people who bend well will probably never have a back problem, while people who bend poorly almost certainly will. It's very important to get bending right!

Hugh Jackman rounding his back while bending

- Don’t Round the Upper Back.

Rounding the upper back is problematic for an entirely different reason. The discs in the upper back don’t generally herniate or get severely damaged. This is partly because the rib attachments to the thoracic vertebrae help fortify that portion of the spine. The problem that results from repeatedly rounding the upper back while bending is that the spinal ligaments gets distended.

Avoid rounding your back and letting your shoulders come forward while bending

Ligaments are like band-aids that go from bone to bone and whose function is primarily structural support. They are a backup system for our muscular support. In situations when there is more challenge and distortion than our muscles are strong enough to handle, or when muscles don’t have time to fire, such as in a jolting accident or jump, then the ligaments keep our joints safe.

Ligaments are supposed to have some degree of stiffness. Ligaments aren’t an elastic kind of tissue. Once stretched too far, they are permanently distended, and no longer serve their role as the backup system to support the spine. Extreme forward bends that come from the back and not the hips cultivate ligamentous laxity more than muscular flexibility. It is counterproductive and results in losing important structural insurance. This is what we see happening in the backs, hips, and knees of athletes and yogis who push too far in poorly executed forward bends as well as other distortions.

Charlotte Bell, an Iyengar yoga teacher and author of Mindful Yoga, Mindful Life, had a hip replacement in 2015. She warns us “I know a number of serious practitioners who are now in their 50s—including myself—who regret having overstretched our joints back in the day. All too many longtime practitioners now own artificial joints to replace the ones they overused.”

- Don’t bend with your legs internally rotated and/or tail tucked

When the legs are internally rotated (toes and knees pointed inwards), the head of the femur grinds inappropriately against the hip socket (acetabulum), wearing down the cartilage and causing arthritic change.

In 2013, Lady Gaga canceled her “Born this Way” tour due to chronic pain from a severe cartilage tear in her hip. Lady Gaga is known for being health conscious and a yoga enthusiast. Though dancing in high heels night after night certainly puts wear and tear on the body, a yoga practice should support, not exacerbate the problem. “My injury was actually a lot worse than just a labral tear,” she told reporters. “...The surgeon told me that if I had done another show I might have needed a full hip replacement. It took over two years after my surgery to be able to correct my alignment and continue working.”

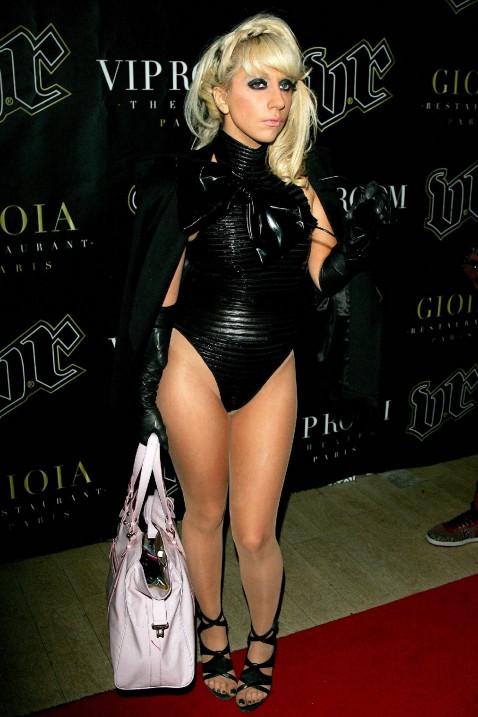

Lady Gaga internally rotating her legs while standing

Lady Gaga bends forward in the yoga pose with toes pointed in and a tucked pelvis.

These pictures of Lady Gaga show that a) she has a tendency to internally rotate her legs while standing and b) she bends forward in the yoga pose with toes pointed in and a tucked pelvis. This puts stress on the hip joint, pushes the ball of the femur into the cartilage of the hip socket, and can overstretch the ligaments of her spine, sacroiliac joint, hip, knee, and foot.

- Don’t push beyond your range of motion in the hips

If you run into resistance in your hip joints when bending, don’t force past it. Dr. Chris Woollam, a Toronto sports medicine physician, says he started seeing “an inordinate number of hip problems” among women aged 30 to 50 who were practicing yoga. “Maybe these extreme ranges of motion were causing the joint to get jammed and some to wear,” Woollam says. “If you start wearing a joint down, then it becomes arthritic. So you’re seeing these little patches of arthritis in an otherwise normal hip that seems to be related to these extremes of motion or impingement or both.”

I suspect that some of the hip problems that get chalked up to extreme range of motion, are actually due to alignment problems. Most yoga classes, Pilates training, and gym routines teach students to stand with parallel feet. By Gokhale Method standards, this constitutes internal leg rotation. Indigenous people have their feet facing outward in the range of 5-15 degrees, and their legs are correspondingly externally rotated. It is our opinion that instructions to have parallel feet contribute to stress and arthritic changes in the hip joints, especially when combined with forward bends and other hip motions.

How well do you stack up when bending in your daily life and when exercising? How far along are you in your hip-hinging journey?

Join us in an upcoming Free Workshop (online or in person).

Find a Foundations Course in your area to get the full training on the Gokhale Method!

We also offer in person or online Initial Consultations with any of our qualified Gokhale Method teachers.

Comments

Robyn Penwell, GM Teacher

Robyn Penwell, Gokhale Method Teacher here. These questions are awesome, and are by no means addressing minutiae.

Esther goes beyond foot placement in her Method and instead teaches foot shape. Honoring the architectural design of the foot allows you to use your feet better (I've learned they are so much more than platforms for standing on!). The action of finding the kidney bean shaped foot not only pivots the foot out slightly, it also lifts the arches and shapes the foot to set up external leg rotation. We want our feet to be arranged well and to be awake and active in standing, bending, and walking. The "awake" part means forming a new partnership with your feet and being mindful about using them actively. A qualified Gokhale Method Teacher will shape your foot for you initially and teach you how to achieve it yourself.

I've found that my healthy kidney bean feet seem to help keep me out of trouble in sports by giving me better natural alignment for knees, hips, and ankles when pushing off, jumping, lunging, or taking off in a sprint. I've had significantly fewer musculoskeletal complaints from sports in my 40's than I did in my 30's before Gokhale Method.

When I took Esther's class years ago as a student, I was so stuck in a Western fitness mindset (I am also a trainer and yoga teacher) that I thought to myself, "What is this bean foot thing? If I don't totally get the idea, it will be OK. I'm taking this class to learn about my back, right?" Boy was I wrong about kidney beaning. After teaching the Gokhale Method for a while now, I have determined it is one of the most essential techniques we teach! I would suggest swinging back around to a qualified teacher to be guided in this important skill.

Best of health,

Robyn

Sacramento, CA

Robyn's post and mine above

Robyn's post and mine above will give you something to work with in addition to what's described in the book and DVD.

Regarding an advanced class, please use our Request a Class in Your Town form - our teachers travel when there are enough requests from a particular place. Also, our teacher population continues to grow - especially for the Advanced classes, it's much easier for a local teacher to teach than have a teacher travel to teach. Please keep letting us know what you would like; we're listening...

Dear Esther and fellow

Dear Esther and fellow teachers,

I so much appreciate this resource and these very clear articles, photos and our discussions about them.

I'm in my second year of Restorative Exercise certification with Katy Bowman. The overall paradigm of the program -- seeing sedentarism for what it is and also focusing on alignment issues and patterns has been greatly beneficial to my work. I'm a Rolfer and dance teacher, plus all-around movement support coach. However, there are aspects to KB's work that I can't understand.

Halfway into my first year of RE I encountered the Gokhale Method. This approach is so sensible and grounded in reality, and so immediately applicable to daily life, that it supplanted the more complex and mental steps that I find accompany many of KB's exercises. Not to take away from her amazing contributions! I just find that Esther's work is accessible in a much more direct way. It radically focused and validated some insights from my previous studies and training, while also highlighting to an uncomfortable point the confusions, contradictions and questions I have.

The foot-knee angle question is probably the best example of this. It's the biggest and most immediately nagging "problem" in my mind. My instinct is to agree with EG on this: observing natural gait in healthy populations we see the slight outward angle. I agree that there are so many aspects to this, including the rotations and counter-rotations in upper and lower limb, as well as pelvic positioning etc.

The forward-tracking kneecap and foot are how we were trained by Ida Rolf's teachers. I've been walking that way for 20 years, without problems, yet I know it is imposed and that I have trained myself to do this.

My question for EG and other teachers: you say that the slight external angle of feet and knees "works best if accompanied by the correct amount of pelvis anteversion (another area of disagreement with Katy and Kelly)." Can you clarify what you mean about correct amount of anteversion and how it differs from Katy and Kelly? I don't know anything about Kelly's work but my sense is that Katy also calls for a certain amount of natural (whatever that means :-)) anteversion. EG, are you saying MORE? or DIFFERENT VERTEBRAL PLACE for the curve? or DIFFERENT in relation to leg bone?

Thank you so much for helping me to understand. I am drawn more and more to GM but still feel a need to "sort things out" in my student mind. Blessings and keep up the fantastic work,

Katie

Hi Katie, Thanks for your

Hi Katie,

Thanks for your comment. Glad to hear that you are seeking!

I'm going to refer you to my post on Forward Pelvis: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly so you understadn my position (I wasn't intending to be punny...) My understanding is that both Katy and Kelly refer to a "neutral pelvis" that has less L5-S1 angle and more upper lumbar curve than what I am describing as normal. It's confusing because, as I describe in the post on Forward Pelvis, people use the same terminology to mean a variety of things.

Don here, 79 years old and

Don here, 79 years old and trying to stay mobile and flexible for a few more years!

I greatly appreciate all the comments here, especially Esther's explanations and of course the original blog post. I have been a fan of Esther's Method for several years, and I have also been following Katy Bowman's work, which I originally got to for the stretching (long neglected by me and much needed). I also have been struck by the difference in recommended foot orientation between Esther and Katy. In a nutshell, I have tried to stretch with Katy feet and to walk with Esther feet. It seems to me that the "best" outward foot rotation for walking is the amount that leads to the heel striking the ground evenly (not on the inside or outside) and also leads to bearing most of the weight on the large pad behind the big toe when pushing off. More outward rotation leads to a heel strike on the outside. Less outward rotation leads to the heel striking on the inside and to putting too much weight on the outside of the ball of the foot, where (especially at my age) there isn't much cushioning to absorb the load, when pushing off. This seems to me to be about 10 to 15 degrees outward rotation, which is in the range that Esther recommends.

In any case, I find Esther's emperical evidence highly convincing. Having been trained and worked in science, I know that experimental results (especially when duplicated repeatedly) always triumph over theoretical results.

I was also very interested to read Esther's comments on thigh rotation, its association with a specific muscle and its relationship to pelvic tilt. It's a SYSTEM!

I would very much appreciate any comments from Esther or others on the utility of my latest tactic for ageing well: barbell weight lifting. This endeavor came from reading a book - The Barbell Prescription, by Jonathon Sullivan and Andy Baker. I am just getting started, but I find the early results very encouraging. Briefly, the idea is that the classic barbell exercises train the motions of life - picking things up, setting things down, pushing and pulling - by working the entire anatomical chain involved, as opposed to the individual muscles. Dr. Sullivan explains in considerable detail how this develops proper body functions at all levels from cellular on up, especially the multiple mechanisms for producing ATP (the energy source on which all body functions depend), and the role of fast-twitch muscles. I was so convinced that I got right into it.

The people in the societies that Esther studies so productively probably "train" these body systems naturally in their daily activities. Those of us who lead relatively sedentary lives need some way to train these systems efficiently. Is "The Barbell Prescription" the answer?

Thank you in advance for your thoughts!

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login