These Glutes Are Made For Walking

Khaddi Sagnia, World Athletics Championships in 2015 - ©Diego Azubel / EPA

Humans have really large butts. Your cat or dog, by contrast, has a very tiny bottom.

Dogs and cats have tiny bottoms

Chances are you’ve never stopped to think about how unique your own derriere is. Primate species are unique in having distinctive buttock anatomy—our buttocks allow us to sit upright without resting our weight on our feet, the way our pets do. Human buttocks, which are particularly muscular and well-developed, empower us to be bipedal, and propel us forward in walking and running. Even if you’re thinking, ‘I don’t have much of a butt at all,’ there’s no comparison between your behind—which has great potential!—and an ape's.

Our primate cousins have similar, but much less-developed gluteal muscles than we do.

Older scientific sources often cite walking as the reason for our large buttocks. Gluteus maximus and medius are important in stabilizing the pelvis and trunk—they keep us from tipping over when we lean into a brisk walk, as well as during older caveman-style activities like throwing and clubbing. (Marzke)

We also know that the gluteal muscles are key for running. The Olympic track and field athletes you’ve been watching in the last few weeks have strong glutes not only for balance, but also to power their bodies across the track, over hurdles, and through the air. All that energy and propulsion comes from the powerhouse of the lower body—the buttocks.

Khaddi Sagnia, long jumper, with well-developed glutes, walking down the track.

I believe that top athletes like Khaddi Sagnia dominate their sports not just from doing reps at the gym and on the field, but also from doing ‘Downtime Training®’—that is, practicing everyday tasks with excellent, natural form. When the glutes are strongly activated in walking, every step is a rep. This is a good example of Downtime Training. As we can clearly see in Khaddi’s example, even her breezy walk down the track prepares her glutes for running and jumping.

Here you can see a video of Swedish long-jumper Khaddi Sagnia, who provides a beautiful example of well developed, active glutes.

Does an ideal walk select for athletic excellence, or does athletic training result in an excellent stride? I believe the two support each other. Someone who already has well-developed muscles from an excellent gait is more likely to excel at sports that involve running, jumping, and lunging; conversely, vigorous use of the glute pack and posterior chain in a sport will predispose a person to have a stronger, better co-ordinated stride. I believe that athletes competing at the Olympic level experience an upward spiral of healthy movement patterns reinforcing athletic excellence, which in turn reinforces healthy movement patterns.

Some recent scientific studies, citing electromyographic (EMG) experiments, have concluded that the gluteus maximus muscle is minimally active in many activities such as walking or climbing stairs, while being highly active during running. In an interview published in Nature about research on how humans evolved to be distance runners, Daniel Lieberman of Harvard claims that running seems to be the only reason that we have prominent buttocks. He has measured the activity of gluteus maximus in volunteers during a walk and a jog and says:

"When they walk their glutes barely fire up. But when they run it goes like billy-o." (Hopkin)

I believe that Lieberman’s finding reflects degenerate modern industrial gait more than it does an evolutionary truth about our species.

Modern-day underdeveloped butt

Lack of glute development accompanied by thoracic kyphosis

Our celebrities are not exempt from the under-developed glute phenomenon, as Taylor Swift demonstrates here.

As we see clearly in the example of Khaddi Sagnia, or other athletes, or indigenous people, or young children, the glutes are in fact actively used in walking and climbing. It’s only in very recent times that we find appreciable numbers of people who barely fire their glutes while walking.

Athletes, like the baseball players above, usually have well-developed gluteal muscles.

Maya White, Esther's oldest daughter, showing the typically toned glutes shared by young children.

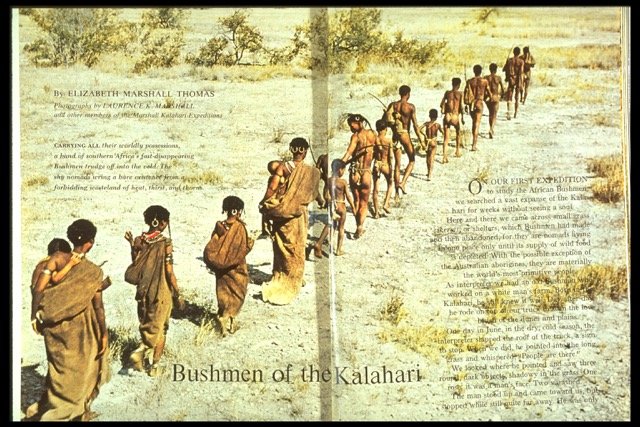

The San indigenous people of the Kalahari, show well-toned glutes from walking and running with primal form.

I teach my students to glidewalk, an ancestral walking form whose mainstay is the activation of the gluteal pack of muscles. Try standing before a table or desk. Turn your right foot outwards while leaning your torso and pelvis forward. Now lift your right leg out behind you (you can hold the edge of the table for support). Your entire gluteal pack will contract – the hamstrings, gluteus maximus and gluteus medius. This is the action you want to find in every step you take.

There are other muscles that are part and parcel of a healthy gait – the calf muscles help launch the rear leg forward to its destination; the muscles on the underside of the foot help grip and grab contours on the earth – and we share these actions with other animal species. But buttock action is special – it marks us as a species, and as bipedal creatures – and it behooves us to use our butts more than most of us currently do.

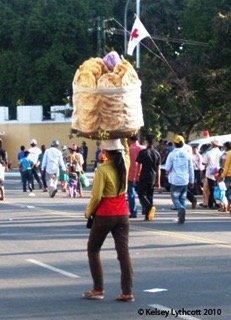

A woman glidewalking in Cambodia

Scientists are right in describing the marked use of the glutes in running, and it is clear their current size is tied to an evolutionary propensity for distance running. Yet it seems unlikely that our ancestors, when they first came out of the trees, hit the ground running. Bipedal walking had to be a predecessor to running while our ancestors mastered balance and being upright. I believe prominently sized butts first developed when our ancestors began to walk upright, and that we want to follow the example of the Olympic athletes in engaging our glutes, not just when we run, but also when we walk. This form of constant training will reinforce healthy posture, as well as strength. And if you’re really lucky, maybe you too will soon be cruising around sporting Olympic hot pants like Khaddi’s. Let us know when that happens - we’ll send our videographer over so we can all enjoy the moment!

Join us in an upcoming Free Workshop (online or in person).

Find a Foundations Course in your area to get the full training on the Gokhale Method!

We also offer in person or online Initial Consultations with any of our qualified Gokhale Method teachers.

References

Bramble, Dennis M., and Daniel E. Lieberman. "Endurance Running and the Evolution of Homo." Nature 432.7015 (2004): 345-52. Web.

Fischer, Frederick J., and S. J. Houtz. "Evaluation of the Function of the Gluteus Maximus Muscle." American Journal of Physical Medicine 47.4 (1968): 182-91. PubMed. Web.

Hopkin, Michael. "Distance Running 'shaped Human Evolution'." Nature.com. Nature Publishing Group, 17 Nov. 2004. Web. 25 Aug. 2016. <http://www.nature.com/news/2004/041115/full/news041115-9.html>.

Lieberman, D. E. "The Human Gluteus Maximus and Its Role in Running."Journal of Experimental Biology 209.11 (2006): 2143-155. Web.

Marzke, Mary W., Julie M. Longhill, and Stanley A. Rasmussen. "Gluteus Maximus Muscle Function and the Origin of Hominid Bipedality." Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 77.4 (1988): 519-28. Web.

Comments

Sit-stand desks are great

Sit-stand desks are great because it is best to have variety in your positions at work. What's equally importnat is to do each position well. It sounds like your standing poistion can use some improvement. Chapter 6 on 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back is all about how to do this. So is one of the segments of my DVD available here through the website. The best way by far to learn anything kinesthetic is with a qualified teacher - with our expanded team of teachers, we're now in a good position to teach you almost anywhere you are.

I took the Gokhale week long

Ouch! This is not usual at

Ouch! This is not usual at all.

1. It's one of our most important directions to NEVER push through pain. Pain is a sophisticated mechanism that evolved to tell you to do something differently. It's important to listen to it! So you needed to stop as soon as you felt any pain - in the first round and the second.

2. Not everyone learns these techniques equally easily. Most people leave the six-lesson course with a toolkit that allows them to continue to make progress after. We recommend doing some maintenance and course-correction work beyond the course - there are a couple of options available for this - in-person group and one-on-one classes, and our Online University. For some, these offerings are critical for honing the basics; for all, they help to not backslide and instead make progress. Online University, in addition to a large library of useful videos to help you review and hone your learning, also includes twice monthly Live Chats with me. You could send photos and / or videos of yourself trying to glidewalk and I would critique them in the group Live Chat (which includes video, audio, text, etc., features). In this way, for the price of less than one private session, you can get customized feedback from me, other teachers, and other alumni of our course, twice a month. Many people have found this very helpful.

3. I took a look at your Before and After photos and I believe that six lessons did not quite do the job for the shifts we like to see. You seem to be trying very hard to have good posture in your After pictures - this work is not done through heroic efforts - it's more about relaxation, stacking bones, appropriate strengthening, and waiting patiently for the shifts to happen. It's not about recruiting one set of muscles to fight another set of muscles. To me, this is good news because even if these concepts didn't entirely land in 6 lessons, they are likely to with a few review lessons.

Sorry your trajectory has been so spectacularly untoward. I' also disturbed that this is the first we are hearing about it. We will have to figure out how to invite more communication earlier when there is a problem. The best place to begin is with your teacher; if that doesn't work, then we need to hear. This blog is probably not the best place to be discussing personal history and you are welcome to delete your post if you prefer. I'm hoping to meet you in one of the Live Chats soon - if you can't find how to do this, contact our customer support and they can explain further details.

I appreciate the reply and I

I woke up thinking about this

I woke up thinking about this (it's a pretty unusual and disturbing occurrence). I noted in your history that you have had "Age 16: Tore ACL & miniscus in L knee, 2 surgeries, one an ACL reconstruction" and that your exercise routine was "non-existant due to back pain." I'm glad your back is better from the course and that you can now (I hope) exercise, but I'm wondering whether due to your previous inactivity and trauma, your Achilles tendons may have been particularly tight. In that case, it may stretch your Achilles tendons too much to leave your rear heel on the ground well into your stride. You may need to take shorter steps and/or let the heel come up earlier until the Achilles tendons stretch out further. There are several other possibilities too...submitting a short video clip of you walking on the Online University Live Chats will help shed light on this.

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login