Don’t Forget the Forgetting Curve! (Part 1)

As a posture teacher, I am very aware of my students’ tendencies to forget the finer points of the Gokhale Method. The longer students wait between classes or refreshers, the more they’ve forgotten. Although there’s always room to improve our teaching methods, forgetting is and will always be a natural phenomenon that accompanies any kind of memory acquisition.

According to nineteenth century psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus and his theory of the Forgetting Curve, people have a steady rate at which they forget material over time. After learning new material, we forget the majority of what we have learned within 24 hours; we forget even more in the following days.

The Forgetting Curve shows how much information we lose, on average, hours, days, and weeks after a learning event.

Normally, discarding much of what we learn throughout the day is an important task for our brains. Most of our memories are useful for the short term, but are not needed by the next day: it’s not crucial to remember what you wore to work last week or what time you walked the dog. To handle all the information you receive throughout the day, your brain purges most of its active memories in order to focus on crucial information. But your brain doesn’t always know how to distinguish the unimportant stuff from important material you want to keep a hold on.

From this article in Learning Solution Magazine on the forgetting curve, we learn that in training programs, “research shows that, on average, students forget 70 percent of what is taught within 24 hours of the training experience.” 90 percent is forgotten within a week. But we also learn that there are ways to let our brains know which information is important, and which isn’t.

Getting ahead of the curve

One method of priming information for long-term memory is through better presentation of material, including using mnemonic devices. Scientists and teachers alike have often found that presenting information using tools like rhyming, patterns, spatial or kinetic cues, or in otherwise relatable ways aids it in being more easily remembered. For example, when teaching tall standing, Gokhale Method teachers use the mnemonic device “three, three, and three.” The symmetry of remembering the steps in threes is a cue that groups related steps into very digestible amounts of information. This technique also helps trigger physical memory, since the three steps always follow in order and move sequentially. Can you recall the three sets of three steps for tall standing, in the feet, lower, and upper body? (Answer: kidney bean feet, feet facing out, weight mainly on heels; soft knees, soft groin, behind behind; ribs tucked, shoulders rolled back, neck tall.)

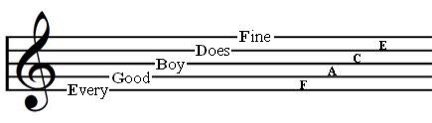

Many of us learned the mnemonic device ‘Every Good Boy Does Fine’ to remember the notes represented by lines on a music staff, and ‘FACE’ for the notes in the spaces.

Multi-channel learning or multimedia learning is another technique that often leads to better memory consolidation and recall. The redundancy principle teaches that presenting non-text images (like animations) at the same time as auditory text helps improve information absorption.

In the Gokhale Method Foundations Course, we present as much of our information as possible with accompanying images to demonstrate the concepts we discuss, and to link the auditory information with visual understanding. We are able to go further than is possible in most academic environments, and add in kinetic and social learning as well. The broad combination of input methods we take advantage of in the course—hands-on instruction, images of good and bad form, instructor demonstrations, repetitive practice, watching other students move and receive adjustment (which hones the eye), commenting on what we see and feel, using tools like a skeleton (sometimes) as well as posture aids like chairs and cushions, feeling our own bodies for physical cues, using anecdotes in addition to medical and historical support (to address the intellectual aspects of the course information)—creates a rich and layered foundation of knowledge to support comprehension and retention.

One reason this multi-channel learning is so powerful is the effect produced by associating newly learned information with previously stored information. This association enables and improves the process of moving information from short-term memory to long-term memory. When we connect something we learn to something we already know, we are actually building upon information retrieval pathways in our brains that we already have practice in accessing. This increases the likelihood that we will succeed in remembering this new information, because we can cue recall by accessing the previously stored information.

We love to take advantage of this association, both by providing the type of rich learning experience discussed above, which increases the chance that students can make personal connections between course info and fields they already have experience in, and by using familiar analogies to explain new concepts. When we talk about hip-hinging, we like to compare the movement to the drinking bird toy:

The drinking bird hinges at the hip without distorting his spine, just like we should! This image helps new students to understand the movement.

When we discuss stretchsitting, we often talk about hanging the back against the back support the way a picture hangs on the wall; in stretchlying on the back we liken our backs to a hammock that contacts the bed one segment at a time, lengthening all the while. Because these analogies are all based on memorable, simple images, they are very easy to both understand and to recall when a student returns to the subject to practice. They help trigger physical memory, because an association has been built between the physical and muscular sensation, and the already-stored image presented in the analogy.

In a future blog post, we will talk about a few more techniques that enable you to get a handle on the forgetting curve, and take charge of your own memory retention. We want you to get the most out of our offerings, so we continue to create tools and opportunities that help students engage with and remember the techniques they learn.

Whether you have read the book, taken the course, or simply subscribe to this newsletter, what are some ways that help you remember to have good posture?

Comments

One of the most potent

Pain is an amazing reminder

Pain is an amazing reminder designed by Nature. If we learn how to read it, it's a powerful tool and guide. If we just slap it away using interventions without pausing to understand it, we're losing opportunities.

The method and it's insights

We've discovered many things

We've discovered many things about the course format over our years of teaching.

I have read the book (and re

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login