Why Does the Oldest Chinese Buddha Figure Slump?

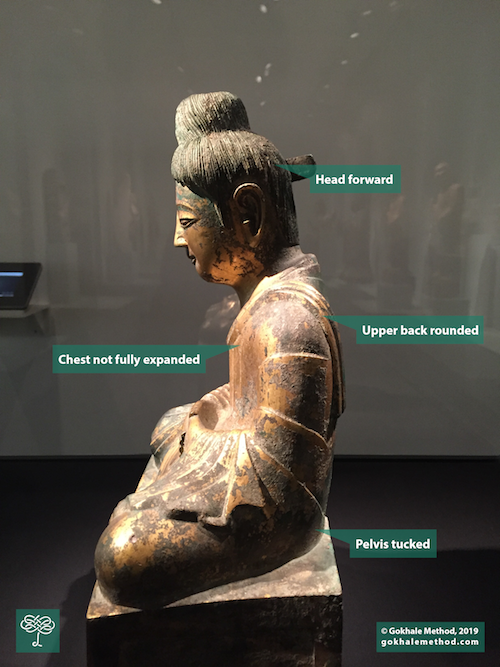

The oldest surviving dated Chinese Buddha figure shows surprisingly slumped posture. Note the forward head, absence of a stacked spine, and tucked pelvis. He would not look out of place with a smartphone in his hand!

This surprisingly hunched Chinese Buddha figure is the oldest dated Chinese Buddha figure that has survived into modern times. The inscription on its base dates it to 338 AD, 500 years after Buddhism came to China from India. Compare the Chinese Buddha figure with this Indian Buddha figure from roughly 800-1000 AD…

This North Indian Buddha figure from the post-Gupta period (7th - 8th century AD) shows excellent form. He has a well-stacked spine, open shoulders, and an elongated neck.

There is a dramatic difference in posture. The Chinese figure looks like a lot of modern folk, whereas the Indian one looks upright and relaxed. Why the difference?

Since the models these figures were based on, and everything and everyone contemporaneous to them are long dead, the best we can do is to make educated guesses about these characters.

India, compared to China, is a warm country. Much of the Indian population sits on the floor cross-legged to gather, eat, play, socialize, and more. To this day, the default praying position is cross-legged without props.

Devotees attending a puja in a temple in Bhubansewar, Orissa.

China, by contrast, is generally a cold country, being further north. It is not comfortable to sit cross-legged on the floor in a cold country, and accordingly, it is common for Han Chinese people to use furniture. In fact, China has many famous styles of furniture, like Ming and Qing Dynasty furniture, and the oldest sitting implements date to earlier than 1000 BC.

This historical northern Chinese furniture dates back to the Liao Dynasty (907-1125 AD). Though they are weathered, the chairs’ armrests, backrests, and seat shape give clues about posture in this period. Original image is licensed by Wikimedia Commons user smartneddy under CC BY-SA 2.5.

As is true in our culture, when people sit on chairs, stools, and benches, the hip socket (acetabulum) is not subject to the same forces as in a person who sits cross-legged on the floor habitually. In my blog post about cross-legged sitting, I use a common-sense argument about why the shape of the hip sockets of someone who grew up sitting on the floor are different from those of someone who grew up sitting on chairs. By the time we are 16 years old, the hip socket is entirely ossified and not amenable to significant shaping or “editing”. For this reason, most modern people from colder climates cannot sit comfortably on the floor for long periods without props. This is also why, I conjecture, this oldest Chinese Buddha figure shows an awkward and uncomfortable posture as he sits cross-legged without props.

I imagine the model for the Chinese Buddha statue to have been a dedicated seeker, eager to embody every aspect of his chosen spiritual tradition. Some of these borrowed aspects would have worked well, probably bestowing on him benefits in his chosen path and practice. The borrowed posture, however, does not help him. He would do better with a prop. If he used a prop to elevate his ischial tuberosities (sitz bones) and let his pelvis tip forward, he would all of a sudden discover that he could be upright without any tension or effort. His back could rise and fall with his inhalations and exhalations. And he would be spared much degeneration and discomfort. My guess is that he had the skills to work with much of his pain, but maybe not all of it, maybe not all the time, and maybe not into his old age. The mind has amazing capabilities to override pain signals, but when those pain signals can be quite addressed at their root with simple mechanical solutions, this is worth learning how to do. The mind can then be used to try to address more unavoidable pain, both physical and emotional.

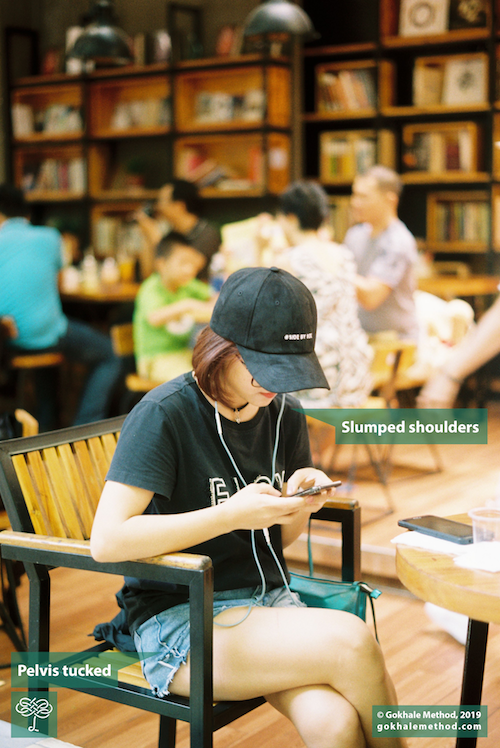

This young woman’s posture, with her protruding head, slumped shoulders, and tucked pelvis, shares many similarities with that of the ancient Chinese Buddha figure. Original image courtesy Andrew Le on Unsplash.

With such slumped posture, my experience indicates that the model’s chest and back would be encumbered by the cantilevered weight of the upper body, and not available for easy expansion. Only the belly is readily available for expansion. The person would learn to soften the belly to allow for easier expansion with the breath. In my imaginings, the belly breathing pattern that started out as a hack could easily get mistaken for a desirable practice to emulate. And this misperception continues into modern times.

If there is any truth to this storyline, the posture demonstrated by the oldest Chinese Buddha figure serves as a cautionary tale. It reminds us that practices develop and thrive in a culturally-specific context. When we import a practice from a different context, it behooves us to consider which portions of the practice can be imported whole, which need modification for local conditions and use, and which need to be edited out of our local version of the practice.

Centuries later, in Japan, Buddhist practitioners invented the zafu, the perfect prop for hip sockets of the kind found in cold countries. A zafu enables a modern meditator to be upright and relaxed, just like the Buddha!

Elevating the seat can make a big difference in meditation posture.

Do you engage in practices you find challenging that are easy in the country of their origin? How have you modified an “imported” cultural practice?

Comments

Lovely post, thanks Esther

Lovely post, thanks Esther.

The story goes, in some schools of Buddhism, that the Buddha only achieved enlightenment (after many years of trying) when a kind young grass cutter brought some freshly-cut grass and made a seat for "the monk" (the Buddha before he was enlightened) to sit on. With his behind slightly elevated and thus his body allowed into a totally upright posture with open chest (chakras all aligned some would say) the Buddha attained enlightenment. This is why a good beginner's meditation class will always focus on helping the sitter to find a good straight and comfortable posture.

Esther, I am also curious about your views on a traditional hammock and whether it is helpful in promoting a J spine?

What a cool interesting story

What a cool interesting story about the Buddha - I had never heard it. If you know where I could research it more, please let me know.

Recently at Kripalu I had the pleaure of experimenting with a hammock. You're supposed to lie diagonally so your body lies straight (instead of cupped). I was able to be very comfortable and rocked to sleep easily by the lake. It wasn't trivial to find the optimal configuration, but possible. I'm sure every hammock is different. Another juicy research project!

Esther, I can't remember

Esther, I can't remember where I first read the story about the grass but I have read/heard many variations over the years. Here is one reference I just found online. Also there is currently a beautiful series on the entire life of the Buddha showing on Netflix, just called Buddha, I highly recommend it to anyone interested, it is wonderful!

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=tZ8WAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA196&dq=grass+cutter+buddha&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjk1Jzo3OviAhUCQH0KHTL0AC8Q6AEIKjAA#v=onepage&q=grass%20cutter%20buddha&f=false

Thanks for this post, Esther.

Thanks for this post, Esther. It was very helpful for me to understand how "belly breathing" came to be recommended. My old Buddhist meditation teacher kept emphasizing a soft, relaxed belly but breathing as you teach always feels better to me. I'm very excited about all of this. Thanks so much. XO

Don't take my hand-waving

Don't take my hand-waving argument as gospel - or dharma! This is just a possible way that belly breathing could become a default - and then an ideal. A little like an S-shaped spine became recognized as normal and then ideal.

In any case, it makes a lot of sense to pay attention to what feels right / better in your body. Glad you're tracking that!

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login