Knee bone connected to the…?

Josephine Baker dances the Charleston

The knee bone is "connected"

to the gluteus medius

Can you sing "Dem Dry Bones"? If you don't know the spiritual by name, I bet you can intone at least some of the lyrics:

…the foot bone's connected to the leg bone, the leg bone's connected to the knee bone, the knee bone's connected to the thigh bone...

Beyond the direct structural connection between the "knee bone," or patella, and the "thigh bone," or femur, is another connection that will be of particular interest to athletes and other individuals afflicted with or susceptible to patellar femoral pain syndrome (PFPS), a disorder often referred to as "runner's knee." And this is the connection between the knee and the gluteus medius, the muscles situated above and toward the outer sides of the much larger gluteus maximus muscles.

How to locate the gluteus medius

If you read my Samba Your Way to Beautiful Glutes post or joined my Samba webinar in November, you'll know how to locate these paired muscles, and you'll appreciate at least some of what they do. (If you'd benefit from a refresher, click and scroll through the Samba post, where you'll find a 6-point list.)

Gluteus medius muscles, pelvic anteversion, and knee health

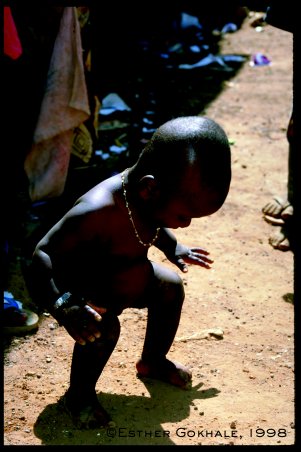

This Burkina baby was patterned to

externally rotate his legs as he was

carried on his mother's back

According to modern conventional wisdom, it's considered normal for young children to have inward-turning knees, which are expected to straighten out by about age 7. What I've observed in village Africa and other nonindustrial cultures is that because children are carried on their caregivers' hips and backs, children's legs are externally rotated from the very youngest ages.

In contrast, in the US and other modern industrial cultures, the internal rotation of the legs is often maintained into adulthood.

Internally rotated legs

Internally rotated legs

are common in modern

industrial cultures, even

in adulthood

Because the gluteus medius muscles are external leg rotators, strengthening these muscles can counter internal leg rotation, helping the kneecaps to align and track better. (To check the tracking of your patella, sit down, place your palm over one of your knees, and then flex your leg to feel and follow the triangular kneecap glide up and down along the end of your femur.) Strong gluteus medius muscles are important because people whose "glute mēds" are underdeveloped are at increased risk of knee and other lower-limb injuries, including patellafemoral pain syndrome. Preventing PFPS, or managing its painful symptoms if the problem has already occurred, are just a couple of reasons why--when you stand, walk, and run--you want to use your glute meds and externally rotate your legs.

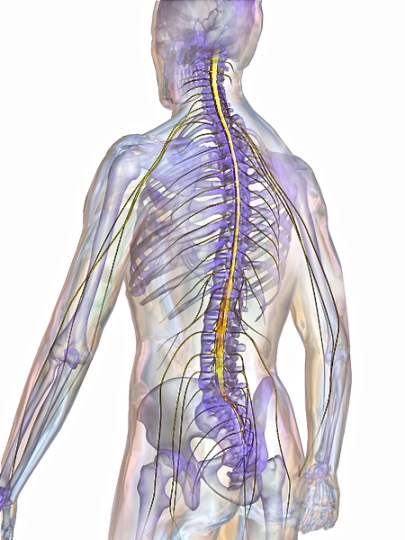

In addition to promoting knee health, external leg rotation

also facilitates an anteverted pelvic position and a

well-stacked spine

Gluteal muscle activity and patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS)

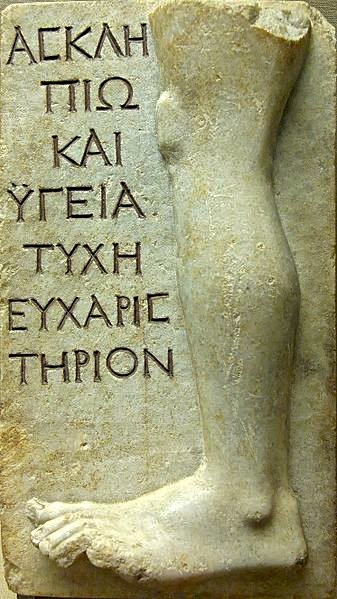

Knee pain is nothing new; this Greek votive

relief for the cure of an injured knee

dates back to 100-200 AD

If you've ever felt a dull, aching pain under or around your kneecap where it connects with the lower end of your femur, you may have experienced patellar femoral pain, especially if the pain occurred when you were sitting for a long stretch of time with your knees bent, or you were kneeling, squatting, or walking up or down stairs.

And, if you have been diagnosed with PFPS, you're not alone. Gluteal Muscle Activity and Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome--A Systematic Review, which was published earlier this year in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, confirms the connection between the knee and the gluteus medius. By synthesizing electromyography (EMG) measurements of the gluteus medius muscles during a range of functional tasks as reported in 10 case-controlled studies, all of which evaluated EMG activity of the gluteus medius, the authors strove to elucidate the relationship between gluteal muscle activity and PFPS. Among their observations and conclusions:

In a nutshell, if you have good strength in your gluteus medius

muscles, your knees will be in better shape.

- Patellofemoral pain syndrome is one of the most common presentations to sports medicine practitioners; of 2500 presentations to sports medicine clinics 25% of all injuries were PFPS

- Individuals with PFPS exhibit reduced gluteus medius and gluteus maximus muscle strength

- Growing evidence supports the efficacy of gluteal muscle strengthening for PFPS and gluteal-muscle strengthening programs have been associated with positive clinical outcomes

Walking is connected to healthy knees

Walking is something most of us do a lot, although according to the 2010 study Pedometer-Measured Physical Activity and Health Behaviors in US Adults, the 5,117 steps Americans typically take each day are not enough--and in fact represent thousands fewer steps than those taken by our counterparts in Australia (9,695 steps), Switzerland (9,650 steps), and Japan (7,168 steps). But even if we step just 5,000 times a day, if we engage our gluteus medius muscles with each step, that's still a lot of repetitions to help "re-architecture" our legs and minimize the risk of PFPS.

Ancient Greek coin features Apollo (with anteverted pelvis!

The pelvis serves as our postural foundation, and one of the keystones for healthy postures is to allow the pelvis to be anteverted. When your pelvis is anteverted and your "behind is out behind you," then the whole pack of muscles that includes the hamstrings, the gluteus maximus, and the gluteus medias can work to advantage, strengthening themselves, inducing circulation in the appropriate places, and bearing stress.

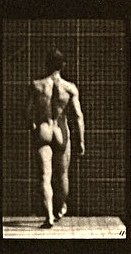

Eadweard Muybridge's 'human male walking'

demonstrates strong gluteal action

in the rear leg

This rear view of the

subject above shows his

healthy external leg

rotation

Beyond this, the relationship between external leg rotation, pelvic anteversion, and the action of the gluteus medius is cyclic. In order for the gluteus medius to be in a position of mechanical advantage, some degree of pelvic anteversion is required. And, if we are to believe the observations summarized in the British Journal of Sports Medicine review, strong gluteus medius action relates to a diminished risk of PFPS.

The interconnectedness between external leg rotation, pelvic anteversion, and strong gluteus medius action is beautifully illustrated in the detail of Muybridge's "animal locomotion" photo and "film" to the right.

"Dem Dry Bones"

Bottom line, the knee bone is connected to the thigh bone, but it's also connected to the gluteus medius, and this is a fairly direct connection because these paired muscles externally rotate the legs. Finally--not just because the lyrics are right on point with this lesson, but because he plays and sings so artfully and with such a great sense of fun--I hope you'll listen to Fats Waller's wonderful take on "Dem Dry Bones."

Join us in an upcoming Free Workshop (online or in person).

Find a Foundations Course in your area to get the full training on the Gokhale Method!

We also offer in person or online Initial Consultations with any of our qualified Gokhale Method teachers.

Image Credits: Josephine Baker Dances the Charleston, Wikimedia Commons; The Bath, Charles Degas, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; How to Locate the Gluteus Medius, Esther Gokhale; X-ray of "Knock Knee," Biomed Central, Wikipedia; The Spinal Cord, Bruce Blaus, Wikimedia Commons; Greek Votive Relief Knee Injury, Marie-Lan Nguyen, Blacas Collection, Wikimedia Commons; Female Jogger, Mike Baird, Creative Commons; Human Male Walking (animation), Eadweard Muybridge, Wikimedia Commons; Animal Locomotion, Eadward Muybridge, Wikimedia Commons; AncientGreek Coin: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc, Wikimedia Commons

Comments

Greetings,In the stance

Greetings,

In the stance called "Horse-Riding Stance" or Ma Bu, used in chinese martial arts (kung fu and tai chi), as seen in the picture below:

http://tajcsi.hu/images/3mabu2.jpg

we need to keep the leg externally rotate in this position, in order to keep the knees pointing outwards, while both feet point forward, because one should avoid letting the knees to "collapse inwards".

So, is it correct to say that this stance is good for strengthening the gluteus medium?

I hope I managed to make my question understandable - I'm from Brazil and my english is not the best.

Pedro Souto

Hi Pedro,Yes, no matter what

Hi Pedro,

Yes, no matter what the feet are doing, externally rotating the upper legs will use, and therefore stregthen gluteus medius.

Interestingly, though your description mentions feet forward, the link you attached shows someone with his feet facing the same direction his knees face. This is the modification I teach in yoga poses, gym workouts, etc. I figure that most peole need some traingin to exteranally rotate their entire leg so why not use time spent exercising to serve towards this...

Your English is great - good luck with your martial arts!

Thank you very much for the

Thank you very much for the answer!

The position of the feet I was talking about is like shown in this picture:

http://www.wutang.org/images/articles/mabu_mabustance_fig2and3.gif

This is the usual guidelines for the Ma Bu stance (Horse-Riding). However, I think the most spontaneous way is letting the feet point outwards (like fig. 2) instead of pointing forward (fig. 3).

Could you comment if you think this recomendation is healthy?

I wish a great new year! I love you work.

Does the same thing apply to

Does the same thing apply to people with IT band syndrome?

The connection is not as

The connection is not as direct as between the knee and gluteus medius, but yes, altering the architecture of the leg affects every tissue in the lower body! That's why in our courses we "cover all bases," rather than hone in on just the problematic areas.

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login