The healthy posture and positive change that antique images can bring to modern people are potentially transformational. In Part 1 of this series we looked at how learning from old photographs can benefit our upper body posture and in Part 2 the lower body.

Here we are going to focus on what antique portraits can teach us about small bends. The historical paintings for this post come from collections associated with Leland and Jane Stanford, famous for their business acumen, political influence, railroad building, and later, philanthropy as founders of Stanford University in California.

Get Updates on the Latest Blog Posts

I developed excruciating lower back pain in 2001. I was a tennis player, downhill skier, and a marathon runner. I was also under a lot of financial pressure in a stressful job as a consumer class action lawyer.

My doctor diagnosed me with a herniated disc at L4-L5. He said that a piece of my disc was sitting on the nerve. I tried everything to stop my pain but nothing worked. In January 2002 I underwent a laminectomy which removed some of the vertebral bone next to the herniation to make room for the nerve root.

This is our fourth blog post in the series where we put popular home exercises under scrutiny to examine how they stack up—or not—against the principles of healthy posture. In this post we are looking at head rotations/circling, an exercise that is often suggested to ease stiffness and mobilize the neck.

Neck pain—causes and solutions

Although not often considered in physical fitness and exercise regimens, the neck frequently becomes a problematic area for people in our culture. At that point, we look to mobilizing, stretching, and strengthening exercises to alleviate pain and stiffness.

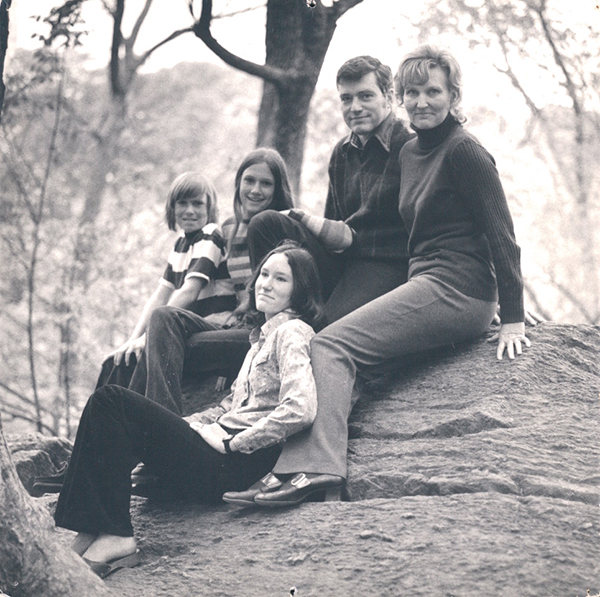

Rediscovering ancestral posture can be fun! In our online 1-2-3 Move program we have had several “Show and Tells” during which participants share old family photographs. The inspiration for healthy posture and positive change that these pictures bring to their descendants, as well as to the online community, is powerful.

In Part 1 of this series we looked at the upper body. Here we are going to consider what our forebears can teach us about healthy alignment for the lower body—specifically, what needs to happen with the pelvis, legs, and feet.

Here I am in September 2017 when I began the Gokhale Method—sitting and bending over:

I have kyphosis. My upper back is curved from the shoulders to the bottom of my ribcage. The exact cause of my kyphosis is not known. There are two types of kyphosis: Scheuermann’s and postural. In Scheuermann’s disease, the normal bone growth in the vertebrae is interrupted during adolescence leading the spine to develop wedge-shaped vertebrae which result in a rounded curve in the thoracic spine. I believe I may have been diagnosed with Scheuermann’s Kyphosis at some point, but I don’t know for sure. I would like to think of it as postural because that word opens up more room for change.

I was born with my left leg and foot turned inward. I wore several different braces on my leg and my foot until the age of five. I became a shy and inhibited child, and I remember not wanting to be seen.

Flexibility in the body is generally regarded as a plus, and most people want more of it. Flexibility is seen to enable a wide range of motion, avoid muscle pulls, and spare wear and tear in overly

When it comes to foot position, feet parallel is often regarded as the ideal in our present-day culture. Standing with the feet apart, pointing straight ahead, is also seen as the starting point of a normal and healthy gait. Walking then proceeds along two parallel lines, like being on railway tracks.

From a Gokhale Method® perspective, a healthy baseline position for the feet is angled outward 5–15°, or “externally rotated.” Why is there such divergence of opinion—and angle?

Most people learn and then teach feet straight ahead

Feet straight ahead is the model learned and perpetuated by most professionals who are trained in anatomy, whether they are fitness coaches, yoga teachers, Pilates instructors, physical therapists, podiatrists, family physicians, or surgeons. Training regimens, gait analysis, shoe design, and equipment such as elliptical trainers and step machines are also based on this belief.

At the beginning of the pandemic, my tween daughter was the dancer in my house. When her in-person hip-hop class was canceled, she quickly turned online for inspiration, showering me with her 30-second Tik Toks.

I was amused, but resolute that dancing online was not for me. I had my own exercise regime, at the heart of which were a series of Pilates-based exercises that I had incorporated in the hopes of healing a nagging injury.

But now, 16 months into the pandemic, I’m dancing online too, maybe even more than my 12-year-old. This is thanks to Esther Gokhale and her unbelievably fabulous community who, like me, wanted to find a safe, therapeutic, and fun way of exercising after injuring our backs.

I first heard Esther years ago on a podcast and subsequently checked her book 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back out of the library. I remember being especially interested in the pictures of women holding their babies so comfortably; I had recently given birth, and I tried my best to imitate the women pictured.

This is our third blog post in the series where we put popular exercises under scrutiny to examine how they stack up—or not—against the principles of healthy posture. Here we are looking at “Cat-Cow,” a common exercise for mobilizing the spine.

Cow is one of the “holy cows” of conventional exercise. Done on all fours, it puts the spine into extension (swaying). It is paired with Cat , which puts the spine into flexion (rounding). Alternating between these postures is widely considered to be a good or even necessary exercise for mobilizing the spine.