Is Belly Breathing Good for You?

It’s common for students to arrive at our classes with strong notions about breathing. Among these is “Belly breathing is good breathing; chest breathing is bad breathing.” I disagree with this widespread belief and present varying amounts of pushback, counterargument, or hints about disagreement depending on the context and how much time I have.

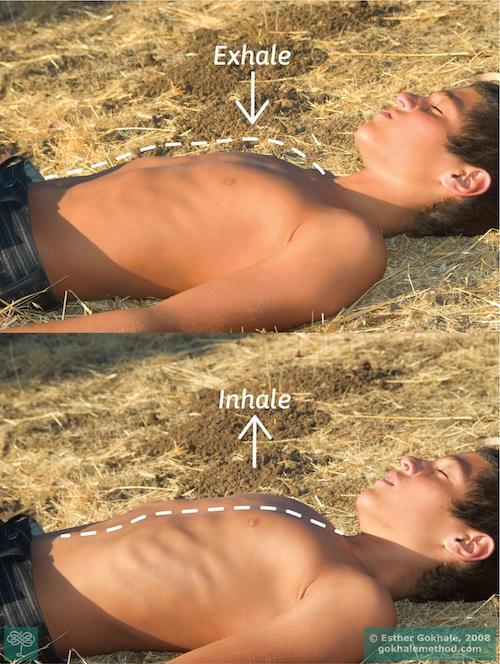

Top: Chest lowered with exhalation. Bottom: Chest expanded with inhalation.

Sometimes I use a hand-waving argument: “Your lungs are housed in your chest; why wouldn’t they expand the chest on inhalation?” Sometimes I argue that if just the belly expands on breathing, that’s usually because the abdominal wall muscles are lax, the long back muscles (erector spinae) are tense, and the intercostal muscles have become stiff from lack of movement. Based on my experience with students, I predict that as the abs become more toned, the erector spinae muscles more relaxed, and the intercostal muscles more malleable, the default pattern of breathing will shift towards chest breathing and back breathing. Belly breathing is important, but only for special situations, like singing and playing the saxophone, where you need control of the diaphragm, or for when you exercise vigorously and need every avenue of expansion available.

Wind musicians, such as this saxophonist, rely upon diaphragm control while playing their instruments.

Photo courtesy Jyotirmoy Gupta.

My main argument that chest breathing and back breathing are normal defaults is the same as my argument for most things in posture: this is the way breathing is done in the populations we are emulating.

Sometimes it is challenging to gauge what a person’s default breathing pattern is. A baby’s breathing pattern varies depending on how she is positioned. We cannot observe ancestral populations live. So, we make observations where possible and best guesses everywhere else.

A baby sleeping on her back naturally defaults to chest breathing.

Photo courtesy Tara Raye.

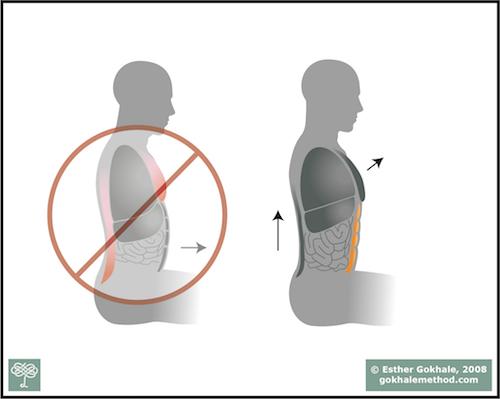

The shape of one’s rib cage gives a clue about the person’s default breathing pattern. I often use the picture below of a carpenter from Burkina Faso, and explain that his expanded chest was shaped by the healthy “stress” of chest-breathing; belly breathing alone could not give him this kind of chest shape.

It takes the healthy stress of breathing in his chest, day in and day out, to fashion his kind of expanded rib cage. His abs are well-toned and don’t “give” as easily as his intercostal muscles and erector spinae muscles do when he inhales.

Back breathing

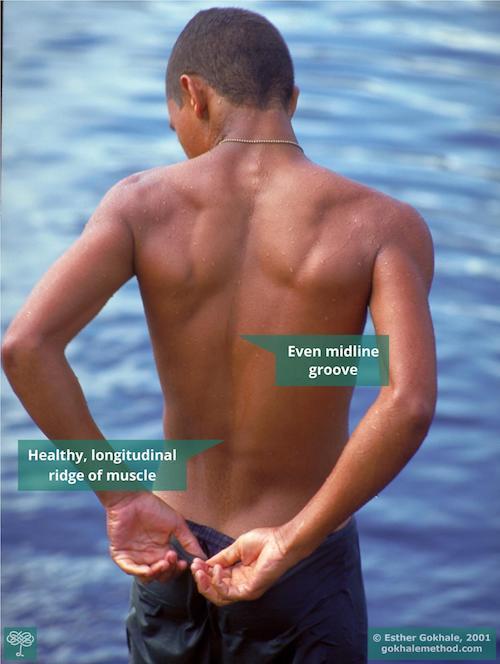

Healthy back musculature is also tell-tale of the natural rise and fall motion of the back that accompanies natural breathing. Nature provisioned us with the ability to keep the tissues around the spine in motion even when we are sedentary. The precious cargo that is contained in our torso is able to enjoy motion simply as a by-product of breathing. But this provision can be undermined by muscle tension in the back, or having the substantial weight of the upper body cantilevered forward. It takes a well-stacked spine and relaxed long back muscles to facilitate the natural motion of the back that accompanies breathing. Conversely, it takes the natural motion associated with breathing to relax and maintain healthy spinal tissues. When I traveled in Burkina Faso, I was struck by the resilient texture of people’s back musculature. And they were struck by a muscle knot in my shoulder I asked input for from a bone-setter (more details in my post Lessons I Learned From My Travels: Burkina Faso). I consider strong but malleable back musculature to be another sign of breathing done right. It’s rare in a modern setting.

This soldier taking a dip in Cachoeira, Brazil demonstrates what healthy back musculature and architecture look like.

Chest breathing vs. neck breathing

I have an educated guess about why chest breathing has gotten a bad rap: chest breathing is easily conflated with “neck breathing” — the anxiety-related breathing pattern that makes one’s shoulders move up with inhalation and down with exhalation. This pattern is, indeed, problematic. It results in tight scalenes, sternocleidomastoid muscles, and other neck/shoulder muscles, and causes pain and dysfunction. But let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater by thinking chest breathing and problematic “neck breathing” are one and the same!

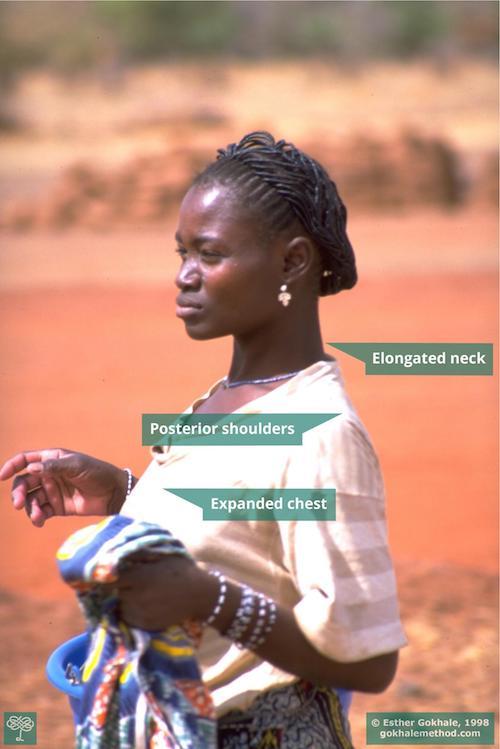

What we really need to do is to isolate chest breathing from neck breathing and enjoy the benefits of chest breathing without triggering tension in the neck and shoulders. We also need to learn to relax the back enough that it can move freely instead of the belly.

Cultivating a deeper awareness of our bodies is a useful feedback mechanism as we begin learning to isolate chest breathing from neck breathing and relax the back. In our Online University for graduates of our Gokhale Method Foundations course and Pop-Up courses, we discuss more advanced techniques for chest breathing. With these techniques, we too can have proud expanded chests and strong resilient backs, instead of aches and pains all around.

This unposed photo of a woman drying her laundry in Burkina Faso shows her expanded chest and healthy rib cage shape. These are a result of normal expansion of the chest with inhalation.

How often do you think about your breathing? Have you been trained to breathe in the chest? Back? Belly? Please share.

Comments

It seems to me that the

It seems to me that the advice (e.g. in meditation practice) to breathe into your belly may derive from a time when anatomy books were not common and an ordinary person was likely to have no idea they had such a thing as a respiratory diaphragm or how it might work. Relaxation of the respiratory diaphragm is essential in promoting the parasympathetic (nurturing) nervous system that is important in achieving a relaxed mind. Thus, in saying "breathe into your belly" the meditation teacher is telling you to relax your diaphragm. If the diaphragm is relaxed and moving freely, the motion of the breath can be felt throughout the body, including into the depths of the belly. That motion is important to the health of the digestive organs. But it is, or should be, subtle.

But the chest is where the lungs are and the whole point of breathing is to get air into the lungs. The motion of the chest in breating is important to the health of the heart and endocrine systems as well as to the health of the spine, as Esther points out so well in her book.

I discovered 8 Steps to a Pain Free Back about six months ago at age 72. After more than 30 years of Iyengar yoga, I was still in the dark (not the fault of my teachers!) as to why my upper body was getting so thin and weak and my back and shoulders hunched. Turns out, I was armoring my compromised lumbar spine by tucking my pelvis, as Esther has described. Sitting or standing, I did not feel the breath in my belly and I also had the sensation of my breath being restricted in my chest. Now following the 8 steps, I can sit upright and feel the gentle wave of motion from my diaphragm into my belly and at the same time feel my chest expanding in all directions and, along with it, I have intimations of courage and compassion I wished for but never expected to have.

Thank you, Esther!

We maybe should remember that

We maybe should remember that the diaphragm relaxes when it goes up, it's most relaxed at the end of the outbreath, if that isn't done though collapsing the chest down. It might not feel like the most relaxed moment, as the deep abdominals (transverse) and some other muscles will probably have more tension at that moment. Sleeping on the belly was mentioned by someone else, I find that position the most conducive to sleep, maybe diaphragm relaxation and improved back/side breathing partly explains this (it also helps avoid tucking the pelvis when sleeping - like Susan, a problem I have to work on).

Interesting article. I love

Interesting article. I love part about muscle disbalance, but on the other hand DNS method is all about belly breathing.

I don't understand how it is

I don't understand how it is even possible to sleep on one's belly without totally torqueing the neck, even with no pillow. What sort of pillow do such people use? The only way I could even consider trying to belly-sleep would be if I were using a special chiropractic bed with a hole for the head letting my face point straight down. I'm now age 65, and my neck has only gotten stiffer in the last few years.

People in some parts of the

People in some parts of the world, and all babies, can bend their necks 90 degrees. For the rest of us a hand or the edge of a pillow placed under the rear part of the skull reduces the need for the neck to turn.

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login