Is Belly Breathing Good for You?

It’s common for students to arrive at our classes with strong notions about breathing. Among these is “Belly breathing is good breathing; chest breathing is bad breathing.” I disagree with this widespread belief and present varying amounts of pushback, counterargument, or hints about disagreement depending on the context and how much time I have.

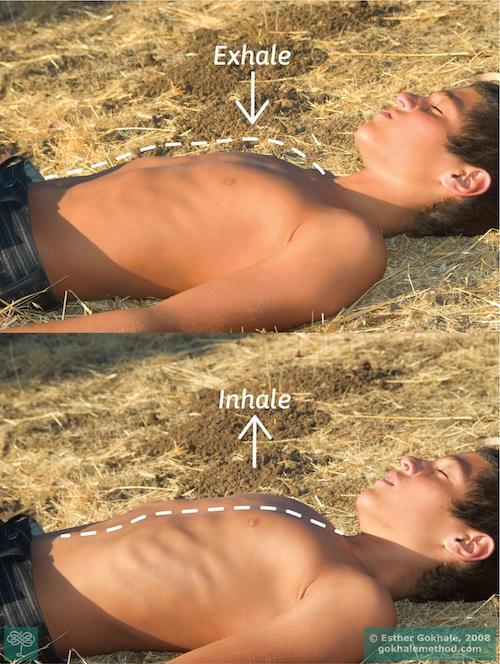

Top: Chest lowered with exhalation. Bottom: Chest expanded with inhalation.

Sometimes I use a hand-waving argument: “Your lungs are housed in your chest; why wouldn’t they expand the chest on inhalation?” Sometimes I argue that if just the belly expands on breathing, that’s usually because the abdominal wall muscles are lax, the long back muscles (erector spinae) are tense, and the intercostal muscles have become stiff from lack of movement. Based on my experience with students, I predict that as the abs become more toned, the erector spinae muscles more relaxed, and the intercostal muscles more malleable, the default pattern of breathing will shift towards chest breathing and back breathing. Belly breathing is important, but only for special situations, like singing and playing the saxophone, where you need control of the diaphragm, or for when you exercise vigorously and need every avenue of expansion available.

Wind musicians, such as this saxophonist, rely upon diaphragm control while playing their instruments.

Photo courtesy Jyotirmoy Gupta.

My main argument that chest breathing and back breathing are normal defaults is the same as my argument for most things in posture: this is the way breathing is done in the populations we are emulating.

Sometimes it is challenging to gauge what a person’s default breathing pattern is. A baby’s breathing pattern varies depending on how she is positioned. We cannot observe ancestral populations live. So, we make observations where possible and best guesses everywhere else.

A baby sleeping on her back naturally defaults to chest breathing.

Photo courtesy Tara Raye.

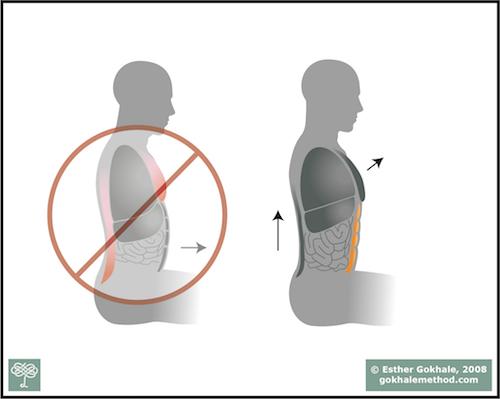

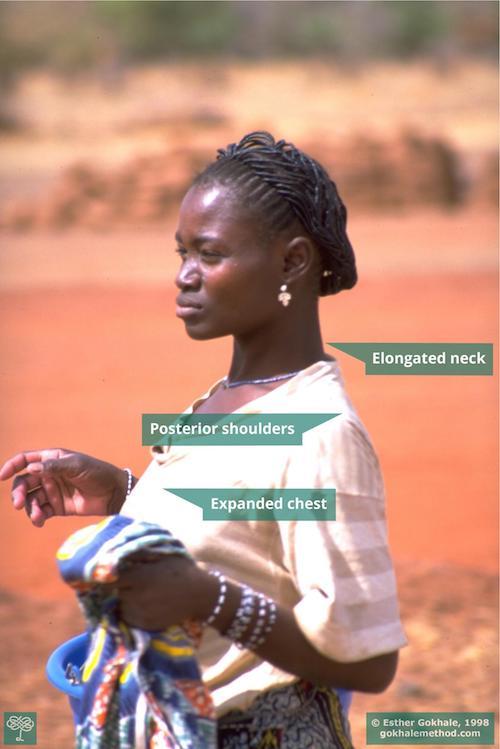

The shape of one’s rib cage gives a clue about the person’s default breathing pattern. I often use the picture below of a carpenter from Burkina Faso, and explain that his expanded chest was shaped by the healthy “stress” of chest-breathing; belly breathing alone could not give him this kind of chest shape.

It takes the healthy stress of breathing in his chest, day in and day out, to fashion his kind of expanded rib cage. His abs are well-toned and don’t “give” as easily as his intercostal muscles and erector spinae muscles do when he inhales.

Back breathing

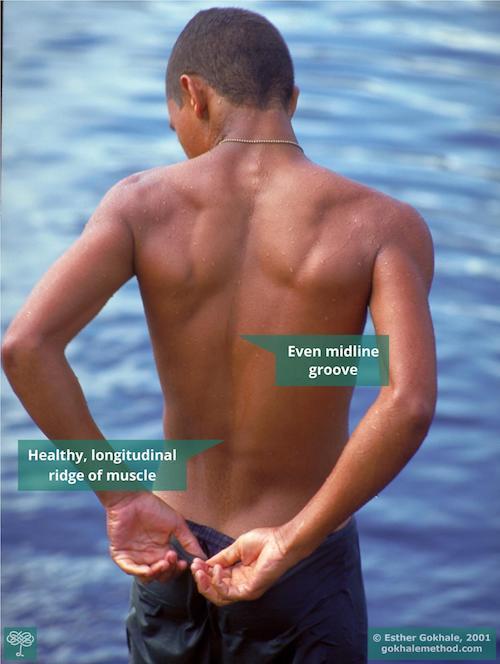

Healthy back musculature is also tell-tale of the natural rise and fall motion of the back that accompanies natural breathing. Nature provisioned us with the ability to keep the tissues around the spine in motion even when we are sedentary. The precious cargo that is contained in our torso is able to enjoy motion simply as a by-product of breathing. But this provision can be undermined by muscle tension in the back, or having the substantial weight of the upper body cantilevered forward. It takes a well-stacked spine and relaxed long back muscles to facilitate the natural motion of the back that accompanies breathing. Conversely, it takes the natural motion associated with breathing to relax and maintain healthy spinal tissues. When I traveled in Burkina Faso, I was struck by the resilient texture of people’s back musculature. And they were struck by a muscle knot in my shoulder I asked input for from a bone-setter (more details in my post Lessons I Learned From My Travels: Burkina Faso). I consider strong but malleable back musculature to be another sign of breathing done right. It’s rare in a modern setting.

This soldier taking a dip in Cachoeira, Brazil demonstrates what healthy back musculature and architecture look like.

Chest breathing vs. neck breathing

I have an educated guess about why chest breathing has gotten a bad rap: chest breathing is easily conflated with “neck breathing” — the anxiety-related breathing pattern that makes one’s shoulders move up with inhalation and down with exhalation. This pattern is, indeed, problematic. It results in tight scalenes, sternocleidomastoid muscles, and other neck/shoulder muscles, and causes pain and dysfunction. But let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater by thinking chest breathing and problematic “neck breathing” are one and the same!

What we really need to do is to isolate chest breathing from neck breathing and enjoy the benefits of chest breathing without triggering tension in the neck and shoulders. We also need to learn to relax the back enough that it can move freely instead of the belly.

Cultivating a deeper awareness of our bodies is a useful feedback mechanism as we begin learning to isolate chest breathing from neck breathing and relax the back. In our Online University for graduates of our Gokhale Method Foundations course and Pop-Up courses, we discuss more advanced techniques for chest breathing. With these techniques, we too can have proud expanded chests and strong resilient backs, instead of aches and pains all around.

This unposed photo of a woman drying her laundry in Burkina Faso shows her expanded chest and healthy rib cage shape. These are a result of normal expansion of the chest with inhalation.

How often do you think about your breathing? Have you been trained to breathe in the chest? Back? Belly? Please share.

Comments

I have been using a VPAP

I have been using a VPAP (Variable positive airway pressure) machine for sleep apnea for several years now and was puzzled at the changes I noticed in my daytime breathing. I am breathing abdominally significantly less than before. It feels as if my entire torso expands smoothly with each inhale, and relaxes and lengthens during exhalation. I feel back and abdominal movement, but it's all one natural movement. I had been taught abdominal (and 3-part) breathing in yoga class, and was worried, but this article has encouraged me to trust my body.

Because the VPAP eliminates my apnea and snoring, it's now comfortable to sleep on my back.

Interesting! Thanks for

Interesting! Thanks for sharing your valuable experience!

Hello Esther,I'm coming back

Hello Esther,

I'm coming back to this thread because I don't know where else to ask this.

I was wondering -- could you write a post about good posture while bottle feeding babies (it is not evident to me--my baby's spine often go to a default round shape) and, especially, about helping your child to maintain and hone good posture while learning to sit? My four month old has rapidly started to sit and can even do so to some extent without support, but his back is a bit rounded and his neck is not lengthened, though he has always had strong neck muscles. I can tell that this is part of him strengthening his muscles, but it pains me to see his spine curved and I worry about him developing bad habits. Is there any risk or do all babies acquire good posture on their own? I know you talk about them needing to be held properly. Maybe you could also mention tripod sitting.

Thank you.

Hi EstherI hope you're fine

Hi Esther

I hope you're fine and safe. Gosh, how happy i am, for finding your website! I am a personal trainer and coach of Low Pressure Fitness (hypopressive exercises). My project calls Hugo Loureiro Tailor Made Training and i also work with other methods such as Pilates, Myofascial Release, Garuda Method and Neuromuscular Training. I was preparing a live talk about belly breathing vs thoracic breathing and most information and knowledge, regarding this controversial subject, points to hail belly breathing, as a sort of Holy Graal. In Low Pressure Fitness we emphasize the importance of a multidimensional breathing pattern, by using chest, ribs, shoulder blades and back , to recruite propoperly the thoracic and pelvic diaphragms and the abdominal wall, for a better manage of pressures on the body. I'm very enthusiastic about your point of view and how you expose the importance of thoracic breathing, for a more toned abdominal wall and a less stiff back. I told about you to the main researcher of Low Pressure Fitness, Dr. Tamara Rial. She lives in Newtown (Pensylvania) and she'd be glad to stay in touch with you!

Congrats for your work and for making my day brighter and happier

Hugo Loureiro

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login