J-spine Validated?

It’s rare to find well-preserved Neanderthal skeletal fragments. It’s especially rare to find well-preserved Neanderthal ribs and vertebrae since these bones are more fragile than skulls and limb bones. But ribs and vertebrae are particularly helpful for discerning the shape of this related species’s thoracic cage and spine.

The recent Kebara 2 Neanderthal find (nicknamed “Moshe”), with very well-preserved vertebrae and ribs, was a particularly exciting find. Patricia Kramer, professor and chair of anthropology at University of Washington, has created a 3-D image deducing what the shape of Moshe’s thorax must have been, and there are some surprises. One surprise is especially interesting: the Neanderthal lumbar spine was practically straight! This was a great surprise to the researchers since they were expecting that Neanderthals, who are quite closely related to our species, would surely have the same lumbar spine shape as ours. The researchers’ starting point is the conventional understanding that modern human spines have a considerable amount of curvature throughout the lumbar area. So discovering that the Neanderthal lumbar spine is straight was shocking to them. For those who subscribe to the basic tenets of the Gokhale Method, though, discovering that the Neanderthal lumbar spine is straight is not so shocking. It reaffirms that our close relatives, the Neanderthals, have a similar lumbar spinal shape to what’s actually natural to us (as the researchers would have expected); it also adds to our conviction that the paradigm of the S-shaped human spine is overdue for an overhaul to the J-spine paradigm.

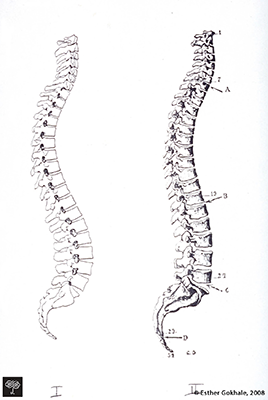

The change in spine depiction from a 1911 textbook (right) to a 1990 one (left) shows that if we travel back in time just a hundred years, straighter spines were thought to be more natural.

A similar situation, described in 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back, comes up with the Laetoli footprints. These show two individuals from 3.7 million years ago walking on a straight line (i.e. the inner heels of both feet touch, but do not cross a line). This finding is used to argue divergence of our species from the species that left behind their footprints. The Gokhale Method claims that walking on two lines is not a natural part of being human, but rather a very recent artifact associated with humans in the industrial age. We have “forgotten” how to walk! One doesn’t have to go very far back, or very far afield, to find modern humans who consistently walk on a line. So the Laetoli footprints instead become evidence of proximity of their ancient owners to us, rather than distance.

The Laetoli footprints (left), dating back to 3.7 million years ago, demonstrate walking “on a line.” This pattern can still be seen in traditional places like modern Brazil (middle), whereas people in industrialized parts of the world have developed a style of walking “on two lines” (right).

It’s not surprising that characteristics as basic as spinal shape and way of walking would be preserved across very long periods of evolutionary history. So this finding is actually not shocking on this score. What’s shocking is that we still don’t know the natural shape of our own spines — and that it takes a Neanderthal to set us straight!

Comments

Dear Esther, Did you send

Dear Esther,

Did you send them this? Or a reference to your book? Because according to the article, these researchers have no clue about real human anatomy, they ONLY know the anatomy of very modern distorted spines.

Since this skeleton appears to be kept a few minutes' walking from my home (at Tel Aviv university), I even thought I'd hop over and show them your book, but wouldn't it be better coming from you personally?

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login