Why Does the Oldest Chinese Buddha Figure Slump?

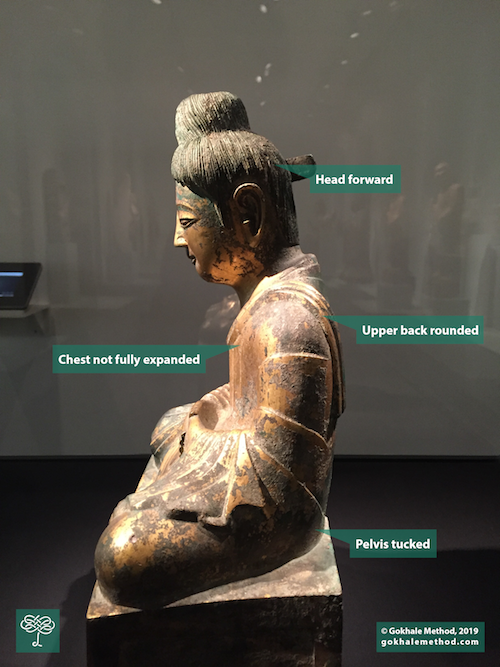

The oldest surviving dated Chinese Buddha figure shows surprisingly slumped posture. Note the forward head, absence of a stacked spine, and tucked pelvis. He would not look out of place with a smartphone in his hand!

This surprisingly hunched Chinese Buddha figure is the oldest dated Chinese Buddha figure that has survived into modern times. The inscription on its base dates it to 338 AD, 500 years after Buddhism came to China from India. Compare the Chinese Buddha figure with this Indian Buddha figure from roughly 800-1000 AD…

This North Indian Buddha figure from the post-Gupta period (7th - 8th century AD) shows excellent form. He has a well-stacked spine, open shoulders, and an elongated neck.

There is a dramatic difference in posture. The Chinese figure looks like a lot of modern folk, whereas the Indian one looks upright and relaxed. Why the difference?

Since the models these figures were based on, and everything and everyone contemporaneous to them are long dead, the best we can do is to make educated guesses about these characters.

India, compared to China, is a warm country. Much of the Indian population sits on the floor cross-legged to gather, eat, play, socialize, and more. To this day, the default praying position is cross-legged without props.

Devotees attending a puja in a temple in Bhubansewar, Orissa.

China, by contrast, is generally a cold country, being further north. It is not comfortable to sit cross-legged on the floor in a cold country, and accordingly, it is common for Han Chinese people to use furniture. In fact, China has many famous styles of furniture, like Ming and Qing Dynasty furniture, and the oldest sitting implements date to earlier than 1000 BC.

This historical northern Chinese furniture dates back to the Liao Dynasty (907-1125 AD). Though they are weathered, the chairs’ armrests, backrests, and seat shape give clues about posture in this period. Original image is licensed by Wikimedia Commons user smartneddy under CC BY-SA 2.5.

As is true in our culture, when people sit on chairs, stools, and benches, the hip socket (acetabulum) is not subject to the same forces as in a person who sits cross-legged on the floor habitually. In my blog post about cross-legged sitting, I use a common-sense argument about why the shape of the hip sockets of someone who grew up sitting on the floor are different from those of someone who grew up sitting on chairs. By the time we are 16 years old, the hip socket is entirely ossified and not amenable to significant shaping or “editing”. For this reason, most modern people from colder climates cannot sit comfortably on the floor for long periods without props. This is also why, I conjecture, this oldest Chinese Buddha figure shows an awkward and uncomfortable posture as he sits cross-legged without props.

I imagine the model for the Chinese Buddha statue to have been a dedicated seeker, eager to embody every aspect of his chosen spiritual tradition. Some of these borrowed aspects would have worked well, probably bestowing on him benefits in his chosen path and practice. The borrowed posture, however, does not help him. He would do better with a prop. If he used a prop to elevate his ischial tuberosities (sitz bones) and let his pelvis tip forward, he would all of a sudden discover that he could be upright without any tension or effort. His back could rise and fall with his inhalations and exhalations. And he would be spared much degeneration and discomfort. My guess is that he had the skills to work with much of his pain, but maybe not all of it, maybe not all the time, and maybe not into his old age. The mind has amazing capabilities to override pain signals, but when those pain signals can be quite addressed at their root with simple mechanical solutions, this is worth learning how to do. The mind can then be used to try to address more unavoidable pain, both physical and emotional.

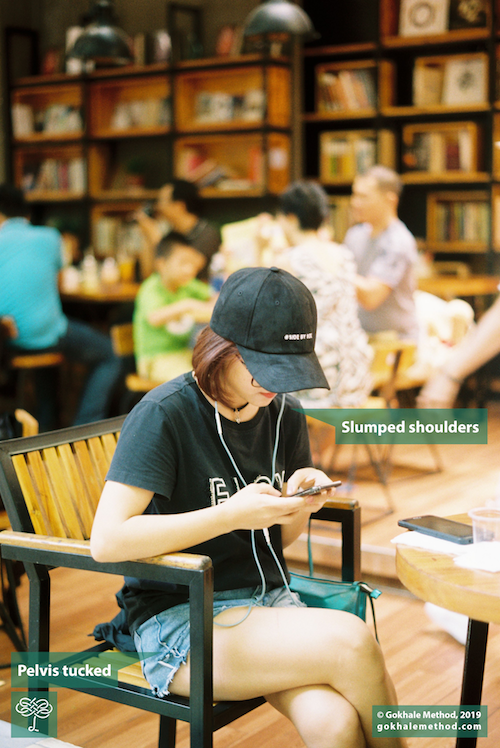

This young woman’s posture, with her protruding head, slumped shoulders, and tucked pelvis, shares many similarities with that of the ancient Chinese Buddha figure. Original image courtesy Andrew Le on Unsplash.

With such slumped posture, my experience indicates that the model’s chest and back would be encumbered by the cantilevered weight of the upper body, and not available for easy expansion. Only the belly is readily available for expansion. The person would learn to soften the belly to allow for easier expansion with the breath. In my imaginings, the belly breathing pattern that started out as a hack could easily get mistaken for a desirable practice to emulate. And this misperception continues into modern times.

If there is any truth to this storyline, the posture demonstrated by the oldest Chinese Buddha figure serves as a cautionary tale. It reminds us that practices develop and thrive in a culturally-specific context. When we import a practice from a different context, it behooves us to consider which portions of the practice can be imported whole, which need modification for local conditions and use, and which need to be edited out of our local version of the practice.

Centuries later, in Japan, Buddhist practitioners invented the zafu, the perfect prop for hip sockets of the kind found in cold countries. A zafu enables a modern meditator to be upright and relaxed, just like the Buddha!

Elevating the seat can make a big difference in meditation posture.

Do you engage in practices you find challenging that are easy in the country of their origin? How have you modified an “imported” cultural practice?

Dear Ester – Your

Dear Ester –

Your studies of posture in pre-modern cultures are very interesting and some parts of your program have been very beneficial for me. However, I think that there are some problems with this analysis. For one thing China is a very big country and vast regions of it are located in tropical and sub-tropical climate zones. Many millions of Chinese make their livelihoods as farmers and spend a lot of time siting on their hunches where they can relax, be close to their work on the ground, and keep their bottoms up above the dirt. This keeps their hips very flexible even if they sit in a chair for super.

Artistic license has made its way into Buddhism and any given sculpture may reflect an ideal as opposed to an actual sitting posture. My immediate impression upon looking at the first figure was that this is the way real people look like when they mediate. If you look closely at the older Buddha, you can see that the top of his pedestal slants forward and elevates his hips above his knees, the same effect as is created by using a zafu. When I saw the second figure my initial impression was that this is an idealized figure of a perfect being.

Because we have a side view of the first figure, and a front view of the second figure, it is hard to compare them, and we have no good idea of what the second figure’s spine looks like. The pictures of the Indians sitting on the ground show that the tops of their spines are bent more forward than the first buddha. The backs of their heads are farther forward from the backs of their shoulders than is the case with the first Buddha. So, he is sitting up straighter. We really can’t see the lumbar regions of the Indian’s backs, to tell if their hips are tucked or not.

I have been practicing sitting mediation all of my adult life and have probably logged around somewhere around 20,000 hours. I am very tall and thin and my shoulders are curved very far forward. Even when I was young and practicing a lot of yoga I have never been able to find a posture that balances the centers of gravity in my upper and lower torso. I go back and forth between stack sitting and stretch sitting but it gets harder as I get older (I am 70). Everything you say about the evil effects of slumped sitting is true but try as I might, for me, sitting upright “without tension or effort” is a cruel joke. I have taught Tai Chi for thirty some years and one thing I have learned is that we must work with our bodies as they actually are, and not merely as we might wish them to be.

On the other hand, your advice about standing has helped me a lot and I am glad I have read your book.

Thanks,

Craig Voorhees

Dear Craig, Thank you for

Dear Craig,

Thank you for your thoughtful post. You speak truth in your statement that "that we must work with our bodies as they actually are, and not merely as we might wish them to be." Another sentiment I air with students is that we don't know enough to gat emotionally charged about what's not "right" in our bodies. As much as I explore and write about posture, I still consider it to be in the realm of conjecture rather than fact. There are very few studies on the subject and the body is complex, so we're all guessing. That said, educated guessing / hypothesizing / exploring can sometimes give great results. So the endeavor continues!

I'd like to add a few thoughts to some of yours:

"Everything you say about the evil effects of slumped sitting is true but try as I might, for me, sitting upright “without tension or effort” is a cruel joke." If the spine has become rigid, it's not possible (or desirable) to straighten it. And the rigid bone supports the structure without muscle tension. I think that's partly why joints become rigid over time. If the structure is not entirely rigid, and if there's enough curvature that it takes an inordinate amount of muscular effort to be upright, I recommend using a backrest / support whenever possible (e.g. in meditation).

"If you look closely at the older Buddha, you can see that the top of his pedestal slants forward and elevates his hips above his knees" An evenly slanted pedestal doesn't give the same abteverted result in the pelvis as a zafu / folded blanket / wedge with a steep dropoff. In the Chinese Buddha figure, it's not quite supporting the pelvis well.

About the difficulty in seeing details in various photo angles and past layers of clothing - so true! I face this difficulty and uncertainty all the time.

A wonderful article Esther,

A wonderful article Esther, thank you.