Middle Eastern Dance: not Belly Dancing, it’s Inner Corset Dancing

This summer, Gokhale Method® teacher Donna Alden stepped in for Lang Liu and brought a unique and enriching twist to our daily 1-2-3 Move program. Drawing on her expertise in traditional Middle Eastern dance, Donna treated us to a beautiful blend of cultural movement and posture wisdom. It’s no coincidence that many traditional dance forms are rooted in healthy, natural posture—and Middle Eastern dance is no exception.

Is this the same as belly dancing?

While often labeled “belly dancing,” this term is both outdated and misleading. Originating in early twentieth century Paris as Danse du ventre (“Dance of the stomach”), it was adapted for Western cabaret audiences and became associated with burlesque and striptease. In contrast, authentic Middle Eastern dance—for example the Egyptian style is known as Raqs Sharqi, or “Dance of the East”—is a deeply expressive and technical art form grounded in cultural tradition and refined body awareness.

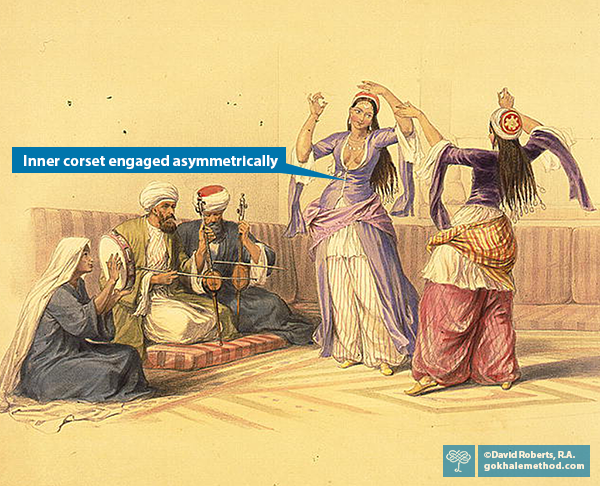

In authentic Egyptian Raqs Sharqi the belly was covered. “Dancing girls at Cairo” (1846–49) by Scottish painter David Roberts.

Taking the inner corset to new depths

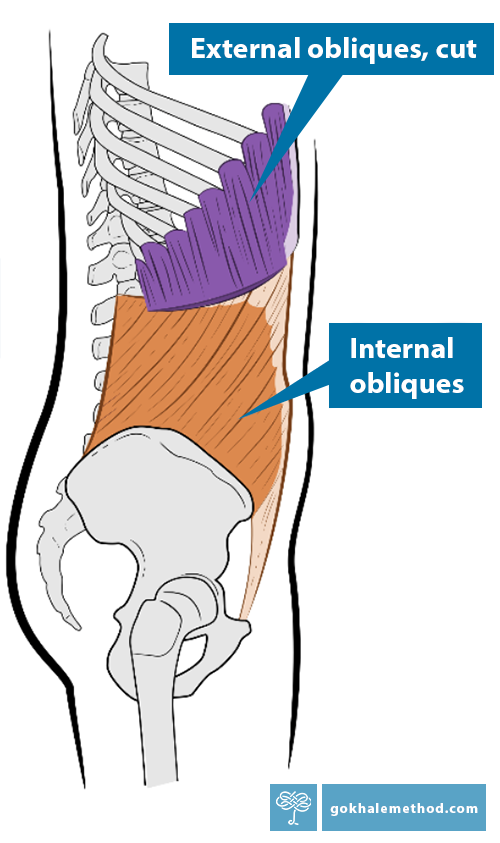

One of the most captivating aspects of Middle Eastern dance is its intricate use of the inner corset—the deep muscles that support the spine and torso. These include the transverse abdominis, inner and outer obliques, multifidus, diaphragm, and pelvic floor. The complexity of their use in Middle Eastern Dance stands apart from many European and South American dance forms, where these muscles contract in unison to keep the torso stable while enabling the limbs to execute rapid, explosive movements. Think of the verticality maintained in Irish step dance or the dynamic footwork of Salsa and Bachata—even when hips are moving, the trunk often stays braced.

The internal and external obliques (cut away) are just two of the many muscle groups and layers that make up our inner corset. The internal obliques are especially important to anchor the front of the rib cage and prevent back sway.

In contrast, in Middle Eastern dance most movement is generated from within the torso itself. The inner corset muscles are activated in precise isolations that can move the pelvis, rib cage, and abdomen independently. Skilled dancers can weave these isolations into mesmerizing figure eights, undulations, hip lifts and drops, circles, shears, and oscillations.

The result? The motion radiates from the inside outward through more fluid, wave-like arms to the fingertips.

Donna dancing on 1-2-3 Move in August. In addition to the fine control of her inner corset, note that she maintains a tall neck, posterior shoulders and a baseline of external rotation in her legs.

A different way to move

To understand how Middle Eastern dance engages the body differently, consider how, in Samba, a hip is often lifted by engaging the gluteus maximus and straightening the leg back—using the large, superficial muscle of the buttocks. This is movement generated from outside of the torso.

In Middle Eastern dance, a hip lift might be initiated by asymmetrical contraction of the quadratus lumborum (QL), a deep muscle that connects the pelvis to the lower ribs and lumbar vertebrae on each side. This inner initiation creates a subtler, more internal movement that looks and feels completely different. It's one of the reasons why this dance form offers such rich opportunities for exploring the body’s deep strength and articulation.

Want to explore inner corset dancing for yourself?

First you want to make sure you have a safe, strong, pain-free baseline of inner corset strength. You can learn this in our in-person Foundations course, one-day Immersion course, or our online Elements course. Our daily Gokhale Active program will help you strengthen your inner corset, refine your rib anchor, and experience joyful, dynamic movement rooted in ancestral wisdom.

Donna found that becoming a Gokhale Method teacher enabled her to use her critical thinking skills (she has a background in both Chemical Engineering and Theology), while further freeing her body from the limitations of scoliosis and back pain. She has now returned to enjoying this artful dance form. As Donna described it:

There is rarely a “great” time to learn new things. I knew when becoming a Gokhale teacher, I did not have excess free time. Between a full-time job, two kids, and a new puppy, I would not have a lot of time in the beginning. At the same time, I know each year as my children grow older, I will have more time and flexibility to engage in my passions.

So, I’m starting small, setting realistic expectations, and driving a wedge in the door of the goal to be a Gokhale Method Teacher. This both gives me pleasure and allows me to share it with others—my wedge of joy, I call it. The hardest part is that first crack.

Best next action steps

You can sign up below to join any one of our upcoming FREE Online Workshops…

Comments

I loved how you wrote about…

I loved how you wrote about the true essence of Middle Eastern dance being much more than “belly dancing.” I was in a Middle Eastern dance company for over twenty years, and our repertoire focused on much more than cabaret styles. The Near East Heritage Dance Theatre performed folk dances from many countries in the region, many of which involved storytelling and interpretive dances of ancient Egypt. Your newsletters have inspired me for many years, and I even have a Gokhale chair! Currently, as a Hanna Somatic Educator, I very much appreciate how you highlighted the various muscles engaged in this dance. It's no wonder I've kept the movements alive in my soma!

I'm also a long-time student…

I'm also a long-time student of Raqs Sharki and I credit this type of dance with keeping me aware, strong and flexible especially in the pelvic area. The Gokhale Method has helped me to orient my spine to keep a healthy connection between upper and lower body movements.

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login