You Want Data? We've Got Data.

Beginning in June 2016, we sent online surveys about lower back pain to all students enrolled in our group 6-lesson Gokhale Method Foundations course. We chose the Roland-Morris Questionnaire [1], and emailed it to students 3 days before, just after, and 4 weeks after the course. All submissions were done anonymously and voluntarily. We are pleased to present our results here.

What is the Roland-Morris Questionnaire?

The Roland Morris questionnaire (http://www.rmdq.org/) lists 24 statements about the influence of back pain on daily activities. Subjects are asked to check a statement if it applies to them on the current day. For each questionnaire, the number of checks marked by the subject is counted.

Why the Roland-Morris Questionnaire?

- It’s a validated and frequently used questionnaire for lower back pain research.

- It is thoroughly tested for sensitivity to changes in lower back pain[2].

- It has been translated into and validated in numerous languages.

- The authors permit online usage of the questionnaire.

Why did the study get done now (what took us so long?!)

Until recently, we did not have the skillset to conduct a conscientious study in house. Our new staff members, Björn Krüger (Computer Science) and Jonas Müller (Physics), have strong academic backgrounds that extend to data analysis. They set up, conducted, and performed the data analysis for the study presented here.

Methods

All students of Gokhale Method Foundations group courses between June 2016 and Jan 2017 were invited to be participants in the study. No exclusion criteria were formulated, as one of the study’s goals is to have our participants demographics fully represented.

Students responded to the surveys on a voluntary basis without any rewards.There was no control group in this study.

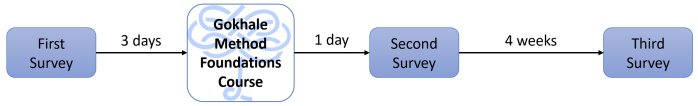

Invitations to fill out the questionnaire were sent out three times via email:

- 3 days before the first lesson of the course,

- 1 day after the last lesson of the course, and

- 4 weeks after the last lesson of the course.

Emails included links to an online questionnaire; the links expired 72 hours after the email was sent.

Fig 1: Method: The survey is based on the Roland-Morris Questionnaire For Lower Back Pain. The questionnaire is filled out by participants three times before and after taking the Gokhale Method Foundations course.

Results

In total, 267 people participated in at least one of the three surveys they were invited to. We received 191 answers to the first survey (S1), 111 answers to the second survey (S2), and 69 answers to the third survey (S3).

The dropout rates in our survey were quite high. We checked for a correlation between initial pain levels and dropout rates and found none.

| Group S1 | Dropout S2 | Dropout S3 |

| No pain (zero ticks) | 65 % | 83% |

| In pain (> 0 ticks) | 68 % | 83 % |

Unpaired test results

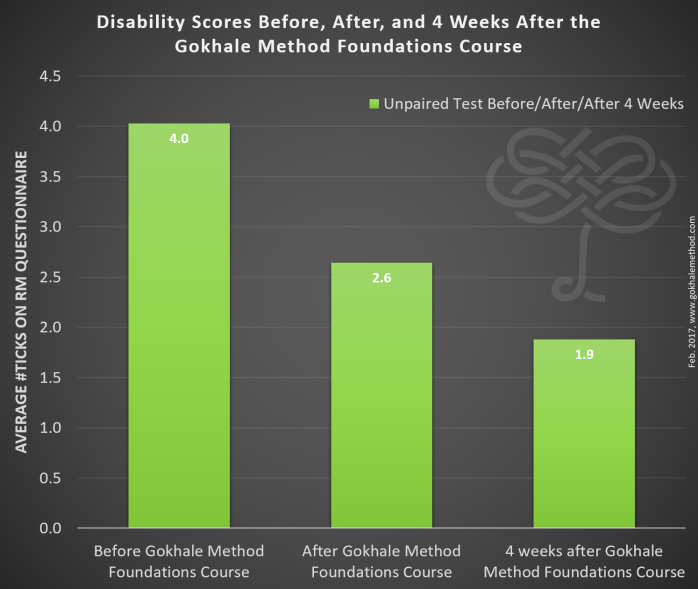

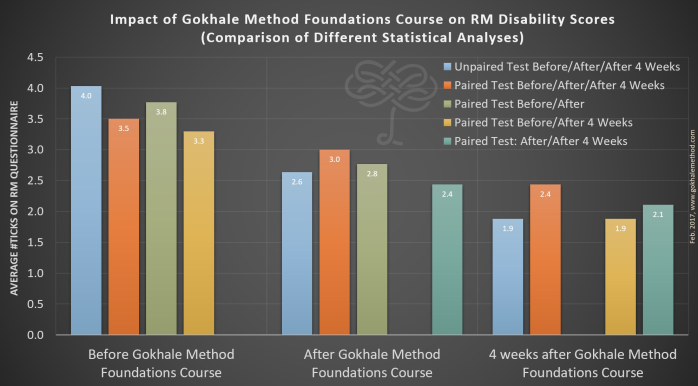

Figure 2 shows, that the mean values of marked ticks dropped from 4.0 in S1 to 2.6 in S2 to 1.9 in S3.

Fig. 2: Change of mean values of number of checked pain-related questions from the Roland Morris Pain Questionnaire due to Gokhale Method Foundations course. Unpaired test.

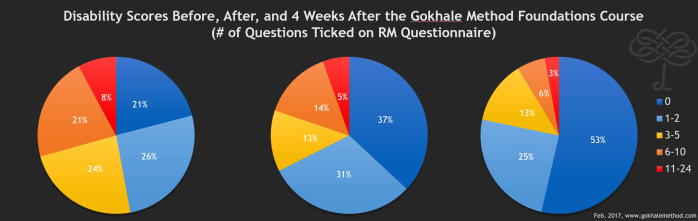

Fig. 3: Pie charts showing the number of ticks in the questionnaire. Before participating in the GMF 21% of the subjects report no lower back pain (dark blue segments), after the GMF it is already 37%, 4 weeks after the GMF 53%.

Figure 3 shows, that the number of people that don’t tick any statement in the questionnaire increases from 21% to 37% up to 53% after four weeks. This reduction in pain levels can also be tracked by looking at the median values: The median drops from 3.0 before the course, to 2.0 after the course to 0.0 after four weeks.

Based on these answers an unpaired test (Mann-Whitney U test) was performed. The p-value between S1 and S2 is 0.0005 (that is to say, the probability that there was in fact no improvement is less than .05%), between S1 and S3 is 7·10-8, and between S2 and S3 is 0.008.

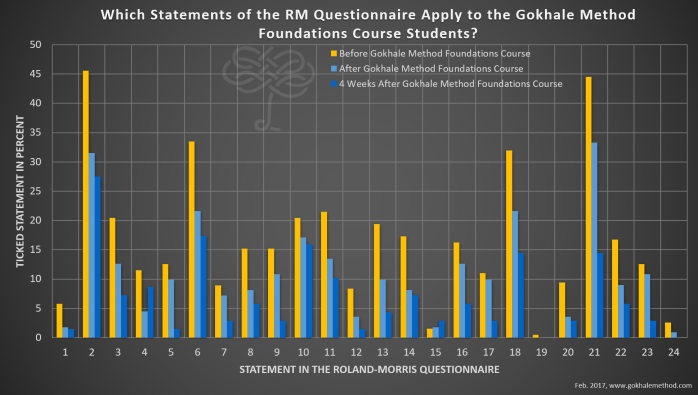

Fig. 4: For each statement of the Roland-Morris Questionnaire, the percentage of participants that ticked the statement is shown. The percentage decreases for most of the statements. The responses to questions 2, 6, 11, 18, 21 show especially large improvements.

Additionally an analysis of improvement in different areas was performed. Figure 4 shows the average number of ticks before, after and 4 weeks after the Foundations Course for each statement of the Roland-Morris questionnaire. The complete list of questions within in the questionnaire can be found at the end of this article.

For most statements the number of ticks decreases over time. Looking at the highest peaks before the Foundations Course, statements 2, 6, 11, 18 and 21 applied to a large percentage of the participants and clearly decrease:

| Qu# | Question | Before GMF | After GMF | 4 Weeks After GMF |

| 2 | “I change position frequently to try and get my back comfortable.” | 46% | 32% | 28% |

| 6 | “Because of my back, I lie down to rest more often.” | 34% | 22% | 17% |

| 11 | “Because of my back, I try not to bend or kneel down.” | 21% | 14% | 10% |

| 18 | “I sleep less well because of my back.” | 32% | 22% | 14% |

| 21 | “I avoid heavy jobs around the house because of my back.” | 45% | 33% | 14% |

The results suggest that participating in a GMF course results in:

- being more comfortable (statement 2./6.),

- becoming more active (statement 11./21), and

- better sleep (statement 18).

Paired test results

62 participants filled the first (S1) and second (S2) survey, 33 participants filled the first (S1) and third (S3) survey, and 27 participants filled the second (S1) and third (S3) survey. 18 participants filled all three surveys.

Two different paired tests were performed. For a pairwise comparison (S1-S2, S1-S3, S2-S3) a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed. The complete set (S1-S2-S3) was subjected to the Friedman test.

Mean values drop by 26% from 3.8 to 2.8 for S1-S2, leading to a p-value for no improvement of 0.0008.

For S1-S3, the mean value drops by 42% from 3.3 to 1.9, with a p-value of 0.006.

Results for S2-S3 show a decrease of 13% from 2.4 to 2.1 with a p-values of 0.28.

The analysis of the complete set results in a p-value for no improvement for the Friedman test of 0.088. The latter two results suffer from low sample size.

Fig. 5: Change of mean values due to GMF. Mean Values for all statistical tests described above. The varying population of participants for the individual tests explains the difference in the presented mean values.

Figure 5 shows the change of mean values of the different paired tests in comparison to the unpaired test. Ongoing surveys will lead to increased sample sizes, smaller uncertainties in paired tests, and more solid results.

Comparison with other interventions

www.healthoutcome.org is a crowdsourcing platform that rates interventions for lower back pain (among other conditions). Among the interventions with over 250 ratings, the frontrunner by a large margin is Postural Modification with a rating of 3.8 out of 5. Among all rated interventions, the Gokhale Method, with 45 ratings, is the top scorer at 4.5. This data, since it is compiled by a third party, and since there is truth in numbers (over 40K ratings collected for lower back pain, a higher number than could ever be contemplated in a controlled clinical trial), deserves serious attention.

Dec. 27, 2017 edit: The Gokhale Method now has 136 reviews (and is still the top scorer), and Postural Modification is now rated at 3.7 out of 5. Interventions now require 500 ratings, rather than the stated 250, to show at the top of intervention lists.

Limitations

The low number of participants in this study limits the variety of statistical methods that can be applied to analyze the data. In future we hope to encourage greater participation in our surveys.

Since all students, irrespective of whether they have any back pain, were invited to participate in the study, the study includes subjects who entered without any lower back pain (see Figure 3). This reduces the initial average back pain rating as well as the magnitude of possible reduction in back pain. In future studies, by including only participants who have back pain, we would expect to see even stronger results in comparison to other clinical studies (e.g. [3] and [4] with mean values of 8 and 10.2).

This study has no control group. We hope that the data we continue to collect, as well as the strong crowdsourced ratings at www.healthoutcome.org will generate interest in a randomized control trial. If you are interested in supporting or conducting such a trial, please contact us at [email protected].

Conclusion

Though our study has limitations, the data suggests that the Gokhale Method Foundations Course has a large positive impact on our students’ lives. The size of this effect appears to be stronger than that reported in studies of other approaches to lower back pain. Given the magnitude of the problem of back pain in modern society, and the dearth of effective solutions, the Gokhale Method Foundation course merits further investigation.

[1] Roland MO, Morris RW. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part 1: Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low back pain. Spine 1983; 8: 141-144.

[2] The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine 2000; 25: 3115-3124.

[3] Lorig KR, Laurent DD, Deyo RA, Marnell ME, Minor MA, Ritter PL. Can a Back Pain E-mail Discussion Group Improve Health Status and Lower Health Care Costs? A Randomized Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(7):792-796. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.7.792

[4] Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA. Comparing Yoga, Exercise, and a Self-Care Book for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:849-856. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00003

Appendix: Questions from the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire for Lower Back-Pain

1. I stay at home most of the time because of the pain in my back.

2. I change position frequently to try and make my back comfortable.

3. I walk more slowly than usual because of the pain in my back.

4. Because of the pain in my back, I am not doing any of the jobs that I usually do around the house.

5. Because of the pain in my back, I use a handrail to get upstairs.

6. Because of the pain in my back, I lie down to rest more often.

7. Because of the pain in my back, I have to hold on to something to get out of a reclining chair.

8. Because of the pain in my back, I ask other people to do things for me.

9. I get dressed more slowly than usual because of the pain in my back.

10. I only stand up for short periods of time because of the pain in my back.

11. Because of the pain in my back, I try not to bend or kneel down.

12. I find it difficult to get out of a chair because of the pain in my back.

13. My back hurts most of the time.

14. I find it difficult to turn over in bed because of the pain in my back.

15. My appetite is not very good because of the pain in my back.

16. I have trouble putting on my socks (or stockings) because of the pain in my back.

17. I only walk short distances because of the pain in my back.

18. I sleep less because of the pain in my back.

19. Because of the pain in my back, I get dressed with help from someone else.

20. I sit down for most of the day because of the pain in my back.

21. I avoid heavy jobs around the house because of the pain in my back.

22. Because of the pain in my back, I am more irritable and bad tempered with people.

23. Because of the pain in my back, I go upstairs more slowly than usual.

24. I stay in bed most of the time because of the pain in my back.

Comments

Add New Comment

Login to add commment

Login