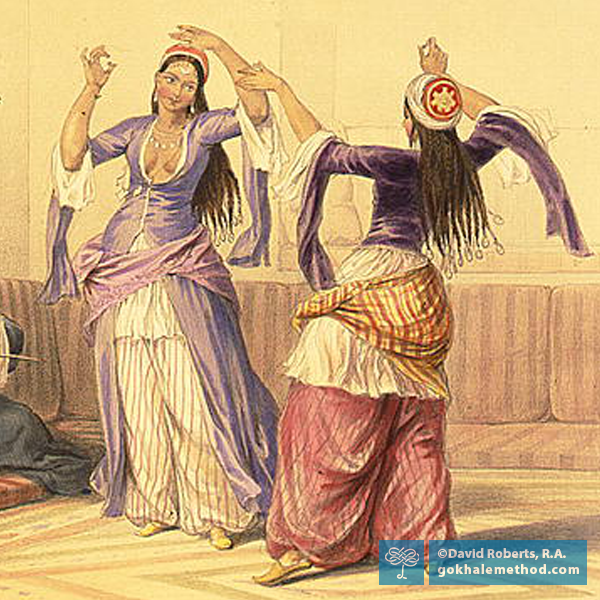

This summer, Gokhale Method® teacher Donna Alden stepped in for Lang Lui and brought a unique and enriching twist to our daily 1-2-3 Move program. Drawing on her expertise in traditional Middle Eastern dance, Donna treated us to a beautiful blend of cultural movement and posture wisdom. It’s no coincidence that many traditional dance forms are rooted in healthy, natural posture—and Middle Eastern dance is no exception.

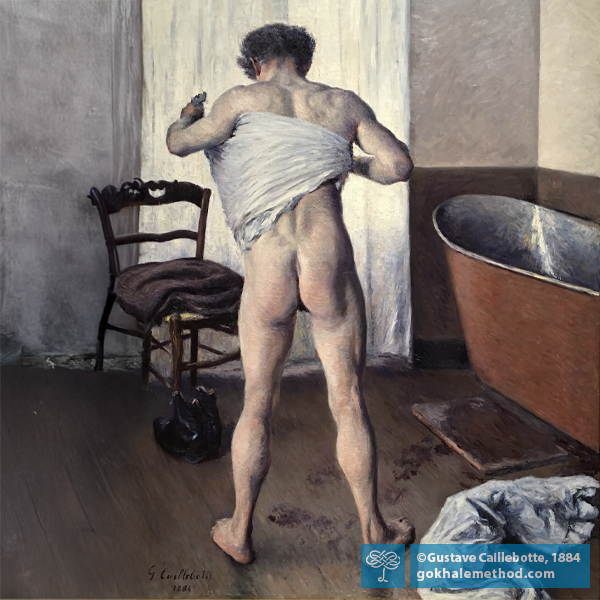

Why Healthy Glutes Reduce Aches and Pains

Over the decades that our students have gotten out of pain by learning the Gokhale Method®, it has become clear that healthy glutes are essential in this. Well-functioning glutes hold the key to unlocking many poor postural habits, and contribute to better biomechanics and movement. Good glute function will often solve pain and enable healing in apparently unconnected areas of the body. Let’s take a look at some of the common, and sometimes surprising, aches and pains that respond to our glute training…

Wake Up Your Glutes, They Snooze, You Lose

In surveys of what people find physically attractive in a partner, a shapely butt is often highly rated. Perhaps it’s no surprise, but if you want, there are even apps to help! So, are good-looking glutes all about sex appeal and filling out our clothing in a flattering fashion? While these concerns may be valid, it is also true that well-toned glutes have many other, profound, but less widely recognized attributes.

This blog post takes a look at the bigger picture of glute function. You may be surprised to find out just how much your glutes can contribute to healthy posture and a pain-free body.

Home Exercises Part 5: Squats

In this blog post, the fifth in our series scrutinizing popular home exercises, we are looking at squats. Is it a beneficial exercise, and how does it stack up—or not—against the principles of healthy posture?

Squats are a popular and effective exercise designed primarily to strengthen the front of thigh muscles (quadriceps), stabilize the knee joint, tone the butt (gluteus maximus), and also work the back muscles.

How to Sit on the Floor, Part 3: Sitting with Legs Outstretched

This is the third post in our multi-part series on floor-sitting. Read Part 1 on floor sitting and Part 2 on squatting!

It’s very common for women in Africa to sit with their legs outstretched. I’ve seen rows of women use this position to spin yarn, engage in idle chatter, sort items, and more. I’ve seen babies massaged by women using this position both in Burkina Faso and in the U.S. by a visiting Indian masseuse who does traditional baby massage in Surat, India. In Samiland I saw this position used to bake bread in a lavoo (a Sami structure very similar to a teepee).

The Sami, who I visited in July 2015 (see my post Sleeping on Birch Branches in Samiland), bake with outstretched legs in

These Glutes Are Made For Walking

Humans have really large butts. Your cat or dog, by contrast, has a very tiny bottom. Chances are you’ve never stopped to think about how unique your own derriere is. Primate species are unique in having distinctive buttock anatomy—our buttocks allow us to sit upright without resting our weight on our feet, the way our pets do. Human buttocks, which are particularly muscular and well-developed, empower us to be bipedal, and propel us forward in walking and running.